ICT4LT Module 2.4

ICT4LT Module 2.4Using concordance programs in the Modern Foreign Languages classroom

ICT4LT Module 2.4

ICT4LT Module 2.4

This is a very large module: around 50 pages. Please wait for it to load completely; it may take several minutes.

This Web page is designed to be read from the printed page. Use File / Print in your browser to produce a printed copy. After you have digested the contents of the printed copy, come back to the onscreen version to follow up the hyperlinks.

The aim of this module is to introduce language teachers to the use of concordances and concordance programs in the Modern Foreign Languages classroom. Concordancing is part of Corpus Linguistics, which is dealt with by Tony McEnery & Andrew Wilson in Module 3.4. Section 2.2 of this module includes a brief introduction to corpus linguistics.

Marie-Noëlle Lamy, The Open University, UK.

Hans Jørgen Klarskov Mortensen, Vordingborg Gymnasium, Denmark.

With an introduction by Graham Davies, Editor-in-Chief, ICT4LT Website.

A “concordance”, according to the Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary (1987), is “An alphabetical list of the words in a book or a set of books which also says where each word can be found and often how it is used.”

I first came across the term “concordance” from one of the lecturers who taught me at university during the early 1960s. He had produced a concordance of the complete works of Stefan George - manually and without the help of a computer. It was a massive and laborious task, during the course of which a good deal was revealed about the writer’s use of language, and it gained the lecturer a PhD. Nowadays such an undertaking would not qualify for the award of a doctorate because a computer can do the job in a matter of hours or - even minutes.

I was introduced to concordancing programs - “concordancers” for short - in the late 1970s, initially using COCOA and OCP, both of which ran on mainframe computers. In the early 1980s I wrote my own concordance program in BASIC on a Prime minicomputer and used it with language students at Ealing College of Higher Education in connection with my classes on text analysis. A version of this concordancer was also incorporated into the 1985 BBC Micro version of Fun with Texts and adapted for the 1992 DOS version by Marco Bruzzone.

Nowadays I often use a concordancer to check my own writing style. It picks up my over-frequent use of certain words, and it is particularly helpful when used in conjunction with a thesaurus. A thesaurus never gives you enough authentic examples of usage to tell you how to use a word with which you are unfamiliar, but a concordancer does - providing you have a decent corpus of authentic texts: see Activity 12 in Section 4.

Concordancers are used extensively these days for creating glossaries and dictionaries, and they are extremely valuable tools for the language teacher but, as Chambers, Farr & O'Riordan (2011:86) point out, there is still considerable resistance among language teachers (both of EFL and of Modern Foreign Languages) to make use of corpora and concordancers. Let’s hope that this module will make a few converts.

The late Tim Johns was one of the first language teachers to draw languages teachers' attention to the use of concordancers in the languages classroom. Back in the early 1980s he began to make use of the concordancers available on the big mainframe computers at the University of Birmingham: Higgins & Johns (1984:88-93). He went on to write one of the first commercially available classroom concordancers, MicroConcord, which was published by Oxford University Press in 1993. Johns also developed the concept of Data Driven Learning (DDL), an approach to language learning whereby the learner gains insights into the language that he/she is learning by using concordance programs to locate authentic examples of language in use. In DDL the learning process is no longer based solely on the teacher's initiative, his/her choice of topics and materials and the explicit teaching of rules, but on the learner's own discovery of rules, principles and patterns of usage in the foreign language. In other words, learning is driven by authentic language data (Johns 1991a); Johns 1991b).

Simon Murison-Bowie, the author of the MicroConcord Manual, gives some very persuasive reasons for using a concordancer, as cited by Rézeau (2001:153) in his chapter on using concordances in the classroom:

Whether one opts for putting up a case, or for knocking one down, any search using [a concordancer] is given a clearer focus if one starts out with a problem in mind, and some, however provisional, answer to it. You may decide that your answer was basically right, and that none of the exceptions is interesting enough to warrant a re-formulation of your answer. On the other hand, you may decide to tag on a bit to the answer, or abandon the answer completely and to take a closer look. Whichever you decide, it will frequently be the case that you will want to formulate another question, which will start you off down a winding road to who knows where (Murison-Bowie (1993:46).

The main advantage of concordancers is summed up by Tim Johns, in reference to a phrase that he frequently used, which I first heard in his presentation at the 1986 Triangle V Colloquium in Paris, namely "the company that words keep":

MicroConcord [...] offers both language learners and language teachers a research tool for investigating "the company that words keep" that has hitherto usually been available only on mainframe computers to academic researchers in such fields as computational linguistics, lexicography, and stylistics (Hockey 1980). (Johns 1986b:121)

"The company that words keep" - a memorable and useful phrase, coined by Firth, as cited by Rézeau (2001:154) in the conclusion to his chapter on classroom concordancing:

It is precisely this "winding road", along which one may come across serendipity learning, which give concordances a certain appeal. In addition, once you have started relying on the evidence of the data for checking the "rules" found in grammar-books as well as your own "intuitions" about language, concordances tend to become an indispensable tool. It is hoped that the rationale and examples given in this chapter will have convinced its readers to take a trip to the country of concordancers to observe "the company that words keep" (Firth (1957:187).

The remainder of this module has been written by Marie-Noëlle Lamy and Hans Jørgen Klarskov Mortensen. Over to them…

Contents of Section 1

What is a concordance? The simplest way to answer this is to look at some English ones to begin with. For instance here is a concordance for the word "sin", prepared manually, and shown with the text from which the four separate occurrences of this word are taken.

Concordance 1 on the word "sin":

|

1. Thus from my lips, by yours, my |

Sin

|

is purged. |

|

2. Then have my lips the |

Sin

|

that they have took. |

|

3. |

Sin

|

from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged! |

|

4. Give me my |

Sin

|

again. |

Text used as basis for the concordance, with the keyword in bold:

JULIET

Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer.

ROMEO

O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do;

They pray, grant thou, lest faith turn to despair.

JULIET

Saints do not move, though grant for prayers’ sake.

ROMEO

Then move not, while my prayer’s effect I take.

Thus from my lips, by yours, my sin is purged.

JULIET

Then have my lips the sin that they have took.

ROMEO

Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged!

Give me my sin again.

So a concordance is a list of words (called keywords, e.g. here "sin"), taken from a piece of authentic language (corpus, e.g. here Romeo and Juliet), displayed in the centre of the page and shown with parts of the contexts in which they occur (here maximum 29 characters to the left of the keyword and to the right). This is also known as a Key Words In Context concordance or a KWIC concordance.

Now look at that same concordance, displayed with fuller context (here between 75 and 80 characters each side, including blank spaces):

|

1. move not, while my prayer’s effect I take. Thus from my lips,

by yours, my sin is purged. JULIET Then have my lips the sin that they have took. ROMEO |

| 2. Thus from my lips, by yours, my sin is purged. JULIET Then have my lips the sin that they have took. ROMEO Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged! |

| 3. is purged. JULIET Then have my lips the sin that they have took. ROMEO Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged! Give me my sin again |

| 4. they have took. ROMEO Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged! Give me my sin again. |

The KWIC and the fuller context display are both useful, depending on what you want to do with the material.

So there you have the basic ingredients for any concordance: a text base and a procedure. But whereas the procedure was manual and it gave us an extremely limited concordance (the concordance had only four citations), the meanings of the word "sin" that appear in it are rooted in the poetic world of Romeo and Juliet. Below, in contrast, is a concordance on the same keyword, based this time on a 25-citation sample created by a concordancer, using contemporary including British and American books, ephemera, newspapers, magazines, radio transcripts and transcriptions of ordinary conversations.

Concordance 2 on the word "sin":

|

1. said cohabiting was no longer a |

sin

|

. Serbs free last six |

|

2. daily care of others was the ultimate |

sin

|

. We arranged for Ted to spend a |

|

3. remarkable. Shaw’s rendition was a |

sin

|

against culture, an insult to Eliot |

|

4. them that God wants them to turn from |

sin

|

and transform their lives. Women |

|

5. the ascendancy to and loss of power; |

sin

|

and redemption; self-doubt and |

|

6. to prove that all that a life of sex, |

sin

|

and St Tropez sun brings is wrinkles |

|

7. taken seriously. Julian’s account of |

sin

|

and forgiveness stands unexcelled |

|

8. deepening anxiety over the question of |

sin

|

and evil, she took it up. Carolly |

|

9. can spring as much from a sense of |

sin

|

as from sanctity. That, thank God, |

|

10. Roebuck was dismissed to the |

sin

|

bin for 10 minutes for his part in |

|

11. is pride, covetousness, deceit and |

sin

|

, but say you’ll accept adultery and |

|

12. is like Sodom and Gomorrah -you know, |

Sin

|

City. So the very word Youngstown |

|

13. of rubber safety bumpers, as ugly as |

sin

|

. Few mourned its passing. [p] That |

|

14. White.26 He finds the earthly ideas of |

sin

|

, guilt, punishment, good and evil |

|

15. BERLIN CABARET NOW Decadence, satire, |

sin

|

… bohemian excess… Once |

|

16. sumptuous food shops. with a sense of |

sin

|

, I bought some on Nevsky Prospekt |

|

17. to mine without a tumble. The only |

sin

|

I’ve committed is not having you |

|

18. sin of all: I have heard of a certain |

sin

|

. I thank God that I do not know of |

|

19. cannot announce God’s forgiveness of |

sin

|

in the Absolution and cannot |

|

20. It was during the Reformation that |

sin

|

in Scotland really got going. Any |

|

21.sin is prevalent. Although this |

sin

|

is a comment on all of mankind, it |

|

22. sounds a bit stage-ethnic: `The only |

sin

|

is to believe that happiness is gone |

|

23. insisting on the concept of original |

sin

|

. It would take on a kind of |

|

24. bed the selfsame one! More primal than |

sin

|

itself, this fell to me. [f] |

|

25. do nothing to deal with her problem of |

sin

|

. Joni was disturbed by Carl’s |

In contrast to the Shakespeare concordance in which the original lines from the play were short enough to fit entirely within the display, here the left and right are chopped off, in this case to 38 maximum characters including blank spaces, a number which in many concordancers can be adjusted to give a less disorienting look to the citations. We will see in Section 5 how important (and also how contentious) the issue of doctoring the results of a search is.

First, for those teachers who like to work with both the target language and the mother tongue, we will say a few words about bilingual or multilingual concordances, also known as parallel concordances. Imagine a novel in Language A and a translation of that text in Language B. Or, in a European context, think of an official document translated into all the languages of the EU. Suppose you want to study how a French word like the preposition "pour" is phrased in different parts of the original texts. Using normal concordancing techniques, the program is able to find all occurrences of pour in French, also identifying the paragraphs and sentences in which those instances occur - e.g. sentence 3 in paragraph 2, sentence 4 in paragraph 3, and so on. Then the parallel concordancer finds the equivalent sentences in the translated text. Preparation of the corpus for use with parallel concordancers has to be meticulous. The two (or more) texts must have been aligned in advance paragraph by paragraph, so that paragraph 3 in one language is equivalent to paragraph 3 in the other (but not sentence by sentence, as we know that translators may well render one sentence by two, or two sentences by one, and so on). Here is an example showing how "pour" relates to various structures in English

A parallel French-English concordance on "pour" using an extract from Le Petit Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupéry

| Original text | Translation |

| 1. Ainsi, quand il aperçut POUR la première fois mon avion [...] | 1. The first time he saw my aeroplane, for instance [...] |

| 2. Alors elle avait forcé sa toux POUR lui infliger quand même des remords. | 2. Then she forced her cough a little more SO THAT he should suffer from remorse just the same. |

| 3. -Approche-toi que je te voie mieux, lui dit le roi qui était tout fier d’être enfin roi POUR quelqu’un. | 3. “Approach, so that I may see you better,” said the king, who felt consumingly proud of being at last a king OVER somebody. |

| 4. Car, POUR les vaniteux, les autres hommes sont des admirateurs. | 4. For, TO conceited men, all other men are admirers. |

| 5. C’est comme POUR la fleur. “ | 5. It is just as it is WITH the flower. |

| 6. C’est donc POUR ça encore que j’ai acheté une boîte de couleurs et des crayons. | 6. It is FOR THAT PURPOSE, again, that I have bought a box of paints and some pencils. |

| 7. C’est le même paysage que celui de la page précédente, mais je l’ai dessiné une fois encore POUR bien vous le montrer. | 7. It is the same as that on page 90, but I have drawn it again TO impress it on your memory. |

| 8. Elle ferait semblant de mourir POUR échapper au ridicule. | 8. She would [...] pretend that she was dying, TO avoid being laughed at. |

| 9. et c’était bien commode POUR faire chauffer le déjeuner du matin | 9. and they were very convenient FOR heating his breakfast in the morning., |

| 10. Il commença donc par les visiter POUR y chercher une occupation et POUR s’instruire. | 10. He began therefore, by visiting them, IN ORDER TO add to his knowledge. |

| 11. Il me fallut longtemps POUR comprendre d’où il venait. | 11. It took me a long time TO learn where he came from. |

| 12. J’avais le reste du jour POUR me reposer, et le reste de la nuit POUR dormir... | 12. I had the rest of the day FOR relaxation and the rest of the night FOR sleep.” |

| 13. POUR toi je ne suis qu’un renard semblable à cent mille renards | 13. TO you, I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes |

MultiConcord is an example of a multilingual parallel concordancer. It is the result of work undertaken at the University of Birmingham as a contribution to an EC-funded Lingua project, coordinated by Francine Roussel, Université de Nancy II, to develop a parallel concordancer for classroom use. Programmed by David Woolls, with Birmingham University support from Philip King and Tim Johns: see MultiConcord and King & Woolls.

ParaConc, published by Athelstan, is another example of a parallel concordancer. See also this Web page at the Athelstan website on Parallel Corpora.

See also St John (2001).

If anyone tries to tell you that this sounds like the sort of work that goes on only at university level, don’t believe them! Secondary school children are quite capable of making use of concordancers, providing you and they are well prepared for the task, as we will try to illustrate in Section 5.

Another interesting use of concordances is to compare texts produced by native and learner speakers of a language. For example, you could put your students’ French or German essays into a concordancer (assuming they had prepared them on a word-processor in the first place), alongside a body of authentic French or German texts. Then you could study how students position words in sentences, and compare this with native speakers. Better still, you could get students to do this comparison themselves, as in Activity 13 in Section 4.

Although powerful professional concordancers can produce many different types of concordances and other sophisticated data, and as such are invaluable to linguistics and literary researchers and to lexicographers, for most teachers KWIC concordances in the target language are quite sufficient to their needs, and the rest of this module will concentrate on those, with some interesting exceptions.

Have a go at creating your own KWIC concordance, using an English keyword of your choice. See our list of online concordancers and corpora below: Websites.

Contents of Section 2

Two things are required to produce a set of Key Words In Context (KWIC):

A simple concordancer produces a list of words it locates in a corpus of authentic texts, displayed in the centre of the page and shown with parts of the contexts in which they occur. This is also known as a Key Words In Context concordance or a KWIC concordance: see Section 1.1. But some concordancers are also able to produce a full concordance comprising all the words and other linguistic elements of the corpus. In reality there are numerous parameters to look for, such as speed, the size of the corpus the software can handle, the languages supported, the amount and quality of the documentation; especially the last point might be important if you are new to concordancing.

It is important to bear in mind that the following presentation of some of the concordancers on the market is not a software review as such but simply a presentation to make you familiar with some of the key features to look for and the screens that you’ll be working with. Trial or demo versions of most of these concordancers are available on the Web. All the necessary information can be found at their websites. Here we’ll only deal with the very basic differences. Pricing also varies a lot - and so does the amount and quality of the documentation.

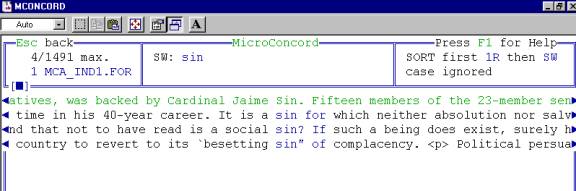

MicroConcord, which was written by Mike Scott (author of WordSmith Tools) in collaboration with the late Tim Johns, set the standard. It was a concordancer written for DOS, dating back to a version originally written for the tiny Sinclair Z80 computer in the 1980s (Johns 1986a; Johns 1986b). It was finally published by Oxford University Press in 1993, together with a substantial corpus of texts from the Independent newspaper and a manual. MicroConcord was impressive for its time, but programs running under DOS are now technically obsolete. The following Figure 1 is a screenshot from MicroConcord.

Figure 1: A screenshot from MicroConcord

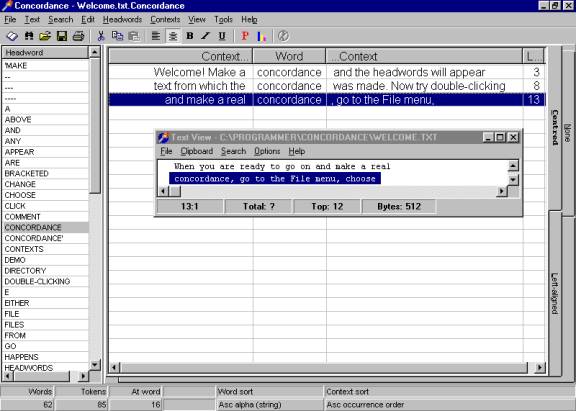

Concordance by R.J.C. Watt of Dundee University makes both a full concordance and a KWIC-concordance, which Watt refers to as a "fast concordance. The fast concordance is really fast. The full concordance is slower. Making a full concordance of a very large corpus requires a lot of computer power and patience.

The user interface is quite intuitive once you have worked a little bit with it. The split screen, with a wordlist on the left and the concordance on the right, is a nice feature. Printing a concordance is possible. This concordancer supports most European languages. Unlike the other concordancers, Concordance is able to convert a full concordance into HTML format so that the concordance can be used interactively through a Web browser. This makes it well suited for literary studies: see Activity 14 in Section 4.

Figure 2: A screenshot from Concordance with “Text view” window opened

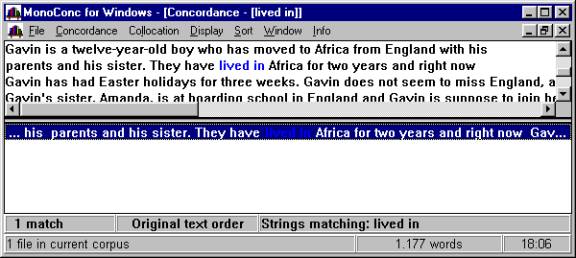

MonoConc by Athelstan is much like a Windows version of MicroConcord. It can only produce single word concordances, but it is very fast indeed, and since it is not so crammed with features the screen layout is very simple to work with. Like the others, this piece of software allows printing of the concordances.

Figure 3: A screenshot from MonoConc

Simple Concordance Program (SCP): Written by Alan Reed, this program is available free of charge. This program lets you create word lists and search natural language text files for words, phrases, and patterns. SCP is a concordance and word listing program that is able to read texts written in many languages.There are built-in alphabets for English, French, German, Greek, Russian, etc. SCP contains an alphabet editor which you can use to create alphabets for any other language. SCP runs both on PCs and Macs.

WordSmith Tools: Concordancer, keyword finder and frequency counter, written by Mike Scott and published by Lexical Analysis Software Ltd and Oxford University Press since 1996. Version 5 (2007) is the latest version.

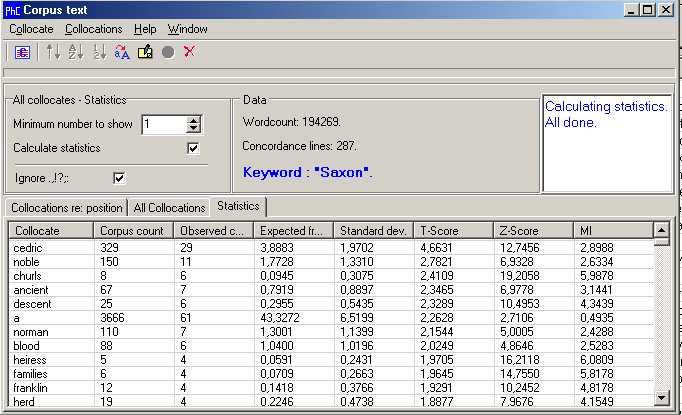

PhraseContext is a different kind of analysis tool. According to the author, Hans Jørgen Klarskov Mortensen, the main idea behind it was not to create yet another concordancer, but to produce a more interactive tool. Most concordancers mainly present results which can be perused on the screen. PhraseContext can export nearly all its results in plain text format, which is directly editable in the small editors that it features. These results can also be sent to the Clipboard, and/or in most cases be saved to a text file. An extension of this is what the author calls a "PhraseBook", a collection of annotated keywords and KWICs. In this way people - and there seems to be more and more of them - who use a specialised corpus as a language reference in their research, can build a collection of linguistic problems they have already solved.

Another of PhraseContext's features is the ability to save wordlists, concordance lines and the PhraseBook to XML-files. This output can be manipulated by means of CSSs and/or Javascript and/or XSL-formatting files for use in Web browsers. So far such scripts are sadly lacking, but the current version of PhraseContext comes with some basic XSL-formatting files.

Besides ordinary concordancing tasks such as word frequency lists, application of stoplists etc, PhraseContext also calculates statistical significance (T-score, Z-score, MI and standard deviation) of collocations and it retrieves clusters of words up to a length of 6 words.

The documentation explains the main features of the software and outlines the necessary linguistic choices the author had to make. References to relevant literature are also included..

Figure 3a: A screenshot from PhraseContext

It is necessary to have some notion of what a corpus is, in order to work with a concordancer. Concordancing is part of Corpus Linguistics, which is dealt with by Tony McEnery & Andrew Wilson in Module 3.4. See also Michael Barlow’s Corpus Linguistics Site.

In this module we will only cover the most basic elements.

A corpus is either just one text or a collection of texts. In Section 1.1 samples of KWIC concordances from Romeo and Juliet are shown. In this case the corpus was Shakespeare’s play. A corpus can also be just one student’s essay. It goes without saying that if the intention is to study the style of, say, Shakespeare the corpus must be limited to his works, but if the intention is to study the grammar and semantics of a whole language, the corpus must contain many texts representing many genres. Likewise: If we want to study 18th-century English we must make sure that the corpus contains a representative amount of texts from the 18th century only. So the contents of a corpus depend on the aims of the user.

How big a corpus one needs also depends on what it is to be used for. Basically the corpus must be so big that there are enough occurrences of the language elements we want to study. The Wordbanks Online corpus comprises about 550 million words and is well suited for linguistic research. Letting our students loose on such vast masses of text is, in most cases, likely to create more confusion than clarity. Far fewer words will often be sufficient. But, of course, if confronted with a really ardent advocate of misguided ideas of what is correct usage and what is not, a failure to find examples of the misguided expressions in a corpus of 550 million words just might make an impression on him/her. Chris Tribble argues that a specialist micro corpus of about 25,000-30,000 words will be quite adequate for most educational purposes. On the other hand, see Tribble and Jones (1997:11): “We tend to think that a word like crime is a common word but it actually occurs only about 20 times in every one million words of a 'balanced" collection of texts such as the Longman-Lancaster corpus”. Later we’ll show examples of what can be done with a corpus of about 50,000 German words.

One of the prime advantages of concordancing in language teaching is the opportunity to use relevant, authentic and interesting examples as opposed to made-up traditional “grammar examples”. This means that if we are trying to teach students how to write an argumentative essay, we should use authentic argumentative texts to teach them the language that such essays call for. And likewise, if the subject is imaginative writing, we should use model texts that fit this genre. How difficult an issue this really is can also be seen from the following example. Recently a Danish publisher released a massive 2277-page English-Danish dictionary based primarily on a corpus of 19th century texts. As one reviewer of the dictionary comments:

“If you are reading Unsworth’s medieval novel from 1995 you will not be able to find “Ostler”, “Tourney”, “Morality Play”, “Lychgate” nor “Mead”. […] If you are reading classical ballads, you will not be able to find “fain”. […] Reading a Bram Stoker short story, Dracula’s Guest, you will not be able to find "he answered fencingly’.”

These examples are more than just a pedant’s protest - they illustrate how vast and complex our languages are (Source: Mogens Kjær: “To-i-en?”, Gymnasieskolen, Nr. 3, 2000, pp. 27ff.).

In a few cases both concordance software and a useful corpus can be found online. Here are some examples:

English and Multilingual

British National Corpus: A very large corpus of modern British English designed to present as wide a range of modern English as possible.

The Compleat Lexical Tutor: An online concordancer and corpora in corpora in English, French, German and Spanish. Many other useful activities too.

Google: Using Google as a simple concordancer, e.g. to check for possible collocations, works quite well. Is is possible, for example, to say "a metal wood"? Yes, indeed! Google cites numerous examples. In German does one say "Ich bin im Internet gesurft" or "Ich habe im Internet gesurft"? Well, both are used, but one form definitely dominates. Enter the whole phrase in inverted commas in Google's search box and you will find hundreds of examples of how the phrase is used. You can use a wildcard (* - the asterisk character) if you are not sure of the spelling of a word or wish to look for two words used together but separated by other letters or words, e.g. a search for ich * habe gesurft (no inverted commas round the phrase) will find "Ich habe gesurft" and "Ich habe gestern mittag noch normal gesurft" - very handy in German when different parts of the verb are separated. Enter the combination ich * habe * Internet * gesurft (no inverted commas round the phrase) and you should find examples such as "Dann habe ich im Internet nach Rezepten gesurft": http://www.google.co.uk/. See Robb (2003).

KWICFinder:

A concordancer that rides on the back of a standard search engine, enabling

the whole Web to be used as a text corpus.

WebCorp: A concordancer that works right across the Web, riding on the back of different search engines. It produces very good results. WebCorp includes a word-list generator that will produce a word frequency list of a Web page in a wide variety of languages. Operated by Birmingham City University, UK.

Wordbanks Online: A corpus that evolved out of the Collins Cobuild Bank of English corpus that forms the basis of the Collins range of dictionaries. The corpus comprises about 550 million words of contemporary written and spoken English. Access is by subscription.

German

Mannheim Corpus: A very big - and free - corpus

of German texts. This includes a choice of corpora and a lot of search facilities.

French

Corpus Lexicaux Québécois: Canadian French corpora

with search facilities.

Other languages

See the references under Websites.

A characteristic feature of online corpora and concordancers is their size - they are in fact very big indeed. They can be used to create your own handouts for your students - or for your own reference. But classroom use of them is perhaps only suitable for quite advanced students who are really interested in linguistic details and who really understand what a corpus is, what the search facilities do and how they work. Later we will show some examples of their use.

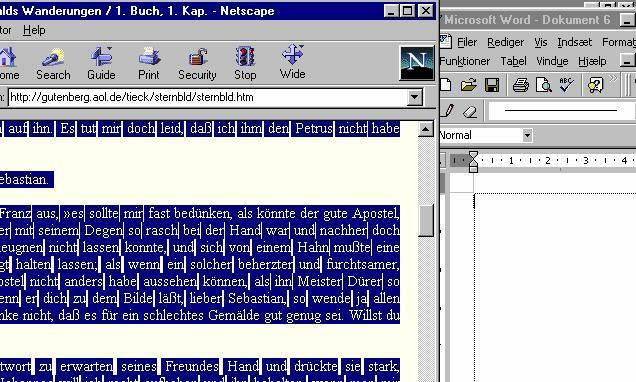

For this project we need a German corpus. Let us suppose that this does not already exist so we will have to make it ourselves. In this case we are only interested in examples of relatively elementary German grammar, so almost any modern German text written by a professional writer will do. We aim to use the Internet to get the texts. This is the step-by-step process:

You can find a corpus by consulting the references under Websites. Or you can go straight to the German Gutenberg Project site, where you will find links to sample texts in German.

Open your browser and go to

the Gutenberg Project site. Reduce the size of the browser window by clicking

on the Restore icon in the top right corner of the screen: ![]()

Figure 4: Creating your own corpus

Click in the browser window. Mark the text you want. Position the cursor in the marked text, click the left mouse button and keep it pressed. Now you can drag the text into the word-processor window. When the word-processor shows a tiny vertical line like this | release the mouse button, and the text is copied to your word-processor!

If for some reason you do not want to use this method you can save the Web pages in their entirety. For example, choose File / Save as…in Internet Explorer. Alternatively, use the Windows Clipboard: mark the text, copy it to the Clipboard and paste it into your word-processor.

CD-ROM

Instead of using texts collected from online sources you can use CD-ROM

encyclopaedias or any other source of electronic text as suggested by Chris

Tribble. The practical method is basically the same as the one described

above in Section 2.2.5.

Texts on

paper

It is also possible to convert texts on paper into machine-readable text.

For this you’ll need a scanner that can convert the printed text into a

computer image. The scanner only makes a digitised image of the text. But a

so-called OCR (Optical Character Recognition) program can convert the

text into machine-readable text. Nowadays good scanners and quite sophisticated

OCR software are quite reasonably priced. Usually OCR software is supplied with

the scanner, and more often than not that software will adequately suit these

needs. Of course scanning and recognising paper texts takes much longer than

just copying them from the Internet, although it may take you time to find what

you want on the Internet.

Typing text

The most time-consuming way of getting machine-readable text is to type

it into a word-processor. But it can be done!

What

format? ASCI or ANSI?

All the concordancers described in this module require plain ASCII/ANSI

text-format and usually the concordancers prefer the text formatted with

CR/LF (a so-called “hard return”) after each line. All modern word-processors

can save in ASCII or ANSI format. Usually you choose Save as… and

then you get a drop-down menu with the different formats.

There is a difference between ASCII and ANSI text format, which is important if you are working with other languages than English. ASCII is the oldest computer text format and was created on the basis of English. ANSI text, a variant of ASCII format, is used by Windows. The advantage is that ANSI text-format includes consistent codes for characters using diacritical signs allowing us to make concordances of all the European languages - and non-European if the appropriate fonts are installed on the computer. The Windows concordancers mentioned above all work with ANSI text-format, whereas MicroConcord (a DOS program) works with ASCII text-format.

Stevens (1995) notices that the corpus preparer may introduce bias into the corpus if he/she “selects data based on preconceived notions of what ought to be there, or on pedagogic grounds”. Is this a tricky issue at all? If so: why? Compare also with traditional grammars and textbooks.

Contents of Section 3

Concordances date back to the Middle Ages, when, like other massive undertakings like Gothic cathedrals or the Bayeux Tapestry, they took up an unimaginable amount of person power. An early example of this, according to Tribble & Jones (1997), is the first known complete concordance of the Latin Bible, the work of some five hundred Benedictine monks working under Hugo de Sancto Charo. Biblical concordances are indexes comprising the words in the Bible and the location of the texts where they can be found. The Encyclopaedia Britannica lists a number of early biblical concordances, including that drawn up by Mercator, the 14th century cartographer. The other favourite corpus of texts for early concordancers, at least in the English-speaking world, is Shakespeare. Encyclopaedia Britannica tells us that Bartlett, the American bookseller and editor best known for his Familiar Quotations wrote, after many years of labour, a Complete Concordance to Shakespeare’s Dramatic Works and Poems (1894), a standard reference work that surpassed any of its predecessors in the number and fullness of its citations.

Because of the canonical status which they have in the culture of the English-speaking world, Biblical and Shakespearian texts have two things in common: they need to be frequently and efficiently accessed, and they have to be interpreted (and reinterpreted). So these early concordances functioned as archiving tools, answering the access need, and as text analysis tools, facilitating interpretation of meanings by bringing words and their contexts into closer proximity on the page, thus sharper focus.

Today’s computerised concordances still fulfil these two functions, the practical and the scholarly. Professional archives, on the Internet or on the intranet in libraries and companies, illustrate the more practical use. For example, if I am a lawyer or a law student, I can access a concordance of legal contexts for the keyword I’m interested in, and I then can assess the currency and coverage of the legal concept under scrutiny. This is clearly of great practical advantage to me. On the other hand, if I am working with language itself, whether as a lexicographer, a translator, a terminologist, a researcher in linguistics, a literary scholar, a language policy specialist, or even perhaps a forensic linguist, I will be interested both in accessing the right texts fast, and in interpreting the language which I discover. So intense is interest in the scholarly application of concordancing that since the 1980ies many national cultures have invested heavily in the creation of great electronic searchable databases, which are real monuments to their language and their literature. For non-English-speaking cultures, such initiatives can also be an important part of their political strategy for linguistic survival.

Search the Internet to find out as much as possible about one of the following great national language corpora. For instance what is it called, when was it set up, by whom, how big is it, what kind of corpus does it use, what are the conditions for access to it, how frequently is it updated, what kind of search facilities does it offer?

French: The ARTFL Project, American and French Research on the Treasury of the French Language

German: The Mannheim Corpus

Italian: The OVI Project (Opera del Vocabolario Italiano)

British English: The British National Corpus

American English (Brigham Young University)

Educational concordancing too has a history, although it is much shorter, having started in the 1980ies. For a summary of its evolution in ELT have a look at Stevens (1995). Claims made for concordancing for educational purposes typically have several facets. One is that concordancers facilitate access to 'real' target language (TL) lexical and grammatical structures. Another is that they can make students more active and independent analysers of language, turning them to an extent into language researchers. The rest of this section looks at how they fit in with current teaching methodologies and practices.

Language teachers want to provide activities and materials that conform with native speakers’ use of the language. The belief is that this is motivational and provides better preparation for learners when they come into contact with written or spoken native speaker utterances. Many traditional grammar books, textbooks and dictionaries contain only invented examples, and that can only reflect the particular ways in which their authors, eminent scholars though they may be, use their mother tongue. However, a language is owned by all its native speakers, not by one small subset, and furthermore, it evolves all the time. But can we as teachers, whether we are trained non-TL speakers or TL native speakers, always claim to have a realistic perception of real usage as it evolves? How many of us have had the embarrassing experience of giving a "rule" to a learner, only to be contradicted by some piece of TL evidence? Sinclair (1986:185-203) encapsulates the teacher’s problem with the comment that we need to “find explanations that fit the evidence, rather than adjusting the evidence to fit a pre-set explanation”. Working with real language data - also called Data Driven Learning (DDL) (Johns 1991a); Johns 1991b) - fits this aim perfectly. DDL allows very easy access to a huge number of extremely varied native speaker productions - although, unsurprisingly, it is a little more difficult to find transcriptions of spoken language. See also Module 3.4, Corpus Linguistics.

However, this raises the question of how prescriptive teachers should be in the choice of TL models offered: it is all very well for French natives to write “des grands bateaux”, flouting the grammar book rule that says it should be “de grands bateaux”, but we should teach grammar book usage or street usage? This question arises in every form of language teaching, but in concordance-based teaching the issue is brought into sharper focus. If the corpus that we use contains unedited material - as it should, if we want to be authentic - then concordancing searches will throw up some questionable usages. There are ways of avoiding this (for example pre-editing the corpus ourselves or using only carefully edited TL texts such as encyclopaedias and other pedagogical texts) but this re-introduces an element of teacher control by the back door and defeats the purpose of exposing learners to real TL forms. Pragmatic decisions will be needed, based on learners’ proficiency levels and teaching objectives.

It is important to provide students with examples taken from real corpora, according to McEnery & Wilson (1996), because “they expose students at an early stage in the learning process to the kinds of sentences and vocabulary which they will encounter in reading genuine texts in the language or in using the language in real communicative situations.” Discuss some arguments in support or in contradiction of this idea (perhaps successively adopting the perspectives of grammar-based teaching and of communicative teaching).

Think about how you would explain the difference between "uninterested" and "disinterested" to (a) native English speakers and (b) non-natives. Use one of the online concordancers and corpora that we list below under Websites to help you determine the difference. How would you use this data to enrich your explanations?

Kettemann (1996) cites the Council of Europe's document (1994:10) concerning the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: "Language pedagogy has hitherto paid little attention to this dimension but should in fact develop explicit objectives and practices to teach methods of discovery and analysis." This, as Kettemann reminds us, is a very good reason why teachers should use computers in the classroom. The computer, he points out, “is a powerful hypothesis testing device on vast amounts of data, […] allows controlled speculation, makes hidden structures visible, enhances at the same time imagination and checks it by inductivity, thus making higher degrees of objectivity possible”. See also Kettemann's article titled "On the role of context in syntax and semantics".

Why would we want a powerful hypothesis-testing device? Because learners need to have tested any rule against as many examples as possible before they can fully internalise it. Why involve the imagination? Because learners remember the knowledge which they have formulated themselves rather than formulations which have been imposed on them.

These are only assumptions, but they have found support in research, see Stevens (1995). Undeniably, whether they are displayed as KWIC lists (like the example of "sin" in Section 1.1) or as columns of matching data (like the parallel concordance example using "pour"), concordance outputs make patterns more noticeable.

Note: Bernhard Kettemann's website is an excellent source of publications on and references to concordancing and corpus linguistics: http://www.uni-graz.at/bernhard.kettemann/

Have a look at Activity 4 (French) or Activity 9 (German) in Section 4, and formulate an empirically-based "rule" for the patterns of behaviour of the word.

Talking about the teaching of linguistics McEnery & Wilson (1996) have remarked:

“In our own teaching we have found that students who have been taught using traditional syntax textbooks, which contain only simple example sentences such as Steve puts his money in the bank […] often find themselves unable to analyse longer, more complex corpus sentences such as The government has welcomed a report by an Australian royal commission on the effects of Britain’s atomic bomb testing programme in the Australian desert in the fifties and early sixties...”

Discuss to what extent this also applies to the teaching of English to non-native English speakers

Communicative teaching coupled with exclusive target language use has undoubtedly brought many benefits to learners but some re-evaluation of its merits is currently taking place. Discussing which language is used in the classroom, Klapper (1998:22-28) approves of “ that revolution which has come over many secondary classrooms in recent years: the use of the FL as the principal language of instruction” but goes on to point out the need to avoid immersion dogmatism. A common L1 in an L2 learning setting is an “obvious classroom resource” which should not be overlooked. Raising learners’ awareness of the TL is linked to raising their mother-tongue awareness, which argues for a reassessment of bilingual (or multilingual) work with learners, and for greater encouragement to learners to "notice" forms, rather than simply use them. In other words, let learners fluctuate between L1 and L2 as appropriate, as this will help them work on the myth that there are one-to-one equivalences between one language and the next, as well as helping them gain a better grasp of what language forms are and get into the habit of discussing them.

Another source of support for the concordancer as a facilitator of language awareness comes from Willis (1999) and his efforts to promote the "lexical syllabus". Challenging the distinction between grammar and lexis, he shows that words should be taught in their "patterns" or "frames". For instance a pattern like the idea (or risk, or thought, or hope) of -ing as the right "feel" for English. Other frames might be possible but simply don’t occur, such as the wish of -ing . Teaching all these words individually, or teaching the rule about of + -ing is not sufficiently helpful to the learner. Willis denies that “words are single items and grammar tells us how these items combine.” For him “Rather than grammar on the one hand and lexis on the other, we have an intricate relationship between the two”. The interrelationship of lexis and syntax is something that jumps off the page or the screen, for anyone who is at all familiar with concordancer searches. KWIC concordances are rich in such patterns as the one Willis mentions, and, given a little dexterity with search techniques, users can easily create large collections of them for further learning.

Language learning pedagogy has for a few years now argued in favour of the development of learner autonomy. For example, by Little (1996) claims that successful language use over time depends on continued language learning, and that to develop proficiency in a second language we need to be ready “to turn almost any occasion of language use into an occasion of conscious language learning”. So good language learning means regularly stepping back from purely communicative activities, and casting a critical eye over one’s own understandings and one’s own strategies. Using concordancers, because they facilitate language awareness, also provide opportunities for such critical activities.

Furthermore, increased exposure to authentic texts has turned teachers (and some students) into more discriminating users of textbooks and led them to question the authority of grammars and dictionaries. McEnery & Wilson (1996) list four separate studies of ESL textbooks that have shown that teaching materials not based on authentic data can be positively misleading to students. Combating the effects of this was one major aims of the Collins Cobuild Bank of English project at the University of Birmingham through the publication of hard-copy corpus-based dictionaries and textbooks like the Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary and the Collins Cobuild English Grammar. But even these tools are edited, and therefore not as useful as a raw concordance for those who like to exert their critical faculties on a piece of language.

What about curiosity, though? Students can be in charge without necessarily growing more curious. For example, they can be given data to manipulate, individually or in groups. Or a group can be asked to create concordances for use as gap-filling tests to set for another group, as part of a competitive game. Classroom applications are numerous, as Section 4 aims to show. But unless these tasks are given a validity other that conferred by the teaching setting, students may well not sustain interest beyond the initial buzz of working with a new piece of software. Student-centeredness implies a large measure of real freedom to choose learning tasks, in this case tasks outside of the teaching context, for instance searching the Internet for texts of real relevance to their individual lives. Teachers willing to grant this freedom will have to evolve pedagogies reconciling student interests (unpredictable and changeable) with the cognitive content of the learning activity (which has to be delivered in a planned and reliable way). Well-thought-out concordancer tasks using as varied a corpus as can be mustered, can offer one way to square this particular circle, particularly if students’ preferences are genuinely allowed to influence the choice of corpus texts.

In this section we aim to provide you with some practical examples of worksheets which you can print and use with your students if you think it’s appropriate, But we have only given you a small selection of what can be achieved. We hope that these examples will act as triggers to stimulate your creativity! Some of the examples are in French, others in English, others in German. In most cases the kind of thinking used in a French example can equally well be used in a Spanish or Swedish context if it is “translated” not only into that language as such but into the grammar, syntax and lexis of that language.

When working with concordances, whether paper-based or interactive, students have to cope within a double set of limitations: their level of language proficiency and their level of familiarity with concordances. When you offer a series of concordance-based exercises you will not always be able to grade them according to both criteria. Our experience is that you cannot overestimate the students’ need for familiarity with the appearance of concordances, and their need for guidance as to how to derive conclusions from lists of citations. One way of ensuring this is to provide plenty of practice with paper-based exercises first, so that students get used to inductive reasoning before they are asked to cope with the additional burden of manipulating a piece of software, however simple it may seem to you. Also, by providing paper handouts in the early stages of classroom work with concordances, you will be able to simplify a little the sometimes startling physical appearance of concordances, so that learners get well used to them and can move on to use the inevitably more complex ones which they will create when they start using concordancers interactively.

In any preparation for teaching it goes without saying that you should try the exercises on guinea pigs before presenting them to a class. But with concordancing, this really becomes essential: your results will depend to a large extent on the composition of your corpus, so be warned and always try activities out first!!

Since a corpus and a concordancer in principle lets you and your students examine almost all aspects of your target language the crucial point is to “discover” ways of making the relevant aspects of the target language appear in the concordances. Or put in a less formal lingo: The teacher’s task in concordancing in the classroom is to ask precisely the right questions.

Contrary to teaching with traditional textbooks, exercise books and grammars the teacher will often discover that a particularly productive “question” or activity brings up material and linguistic facts that neither student nor teacher expected. This calls for another type of teacher-role than the most traditional one(s). We’ll return to that point in Section 6.

|

ACTIVITY NAME AND LANGUAGE |

PURPOSE OF ACTIVITY |

PRESENTATION |

| 1. Guess the mystery word (F) | beginners, lexis | paper,online (LAN) |

| 2. Donc on peut dire que (F) | style, usage | paper, online (LAN) |

| 3. S’agit (F) | derive a rule, grammar | paper, online (LAN) |

| 4. Beware false friends… (F) | lexis | paper, online (LAN) |

| 5. Coffee or tea? (F) | cultural differences | paper, online (LAN) |

| 6. Les Anglais et les Britanniques (F) | political correct, usage, lexis | paper, online (LAN) |

| 7. Changing lifestyles (F) | cultural differences, usage | paper, online (LAN) |

| 8. dürfen and müssen (G) | lexis, usage | paper |

| 9. Preposition am (G) | usage | paper |

| 10. Syntax of adverbs (E) | driving a rule, grammar, syntax, statistics, usage | online (WWW) |

| 11. reason + because (E) | correctness, usage | online (WWW) |

| 12. Students’ own writing (E) | variety, usage | online, standalone PC |

| 13. L’aigle noir (F) | literary analysis | online (LAN) |

| 14. Mariana (E) | literary analysis | online (LAN or WWW) |

Aim of the activity: To familiarise students with the physical appearance of a KWIC concordance and with the importance of left-context and right-context when working with keywords. This is to be used with people who are complete beginners at concordancing.

Worksheet: Read the grid below, where the nonsense word "gloup" has been entered instead of a real word. Your job is to decide with your group what that mystery real word is. When you have made up your mind, discuss with your group what the answers to the three questions listed below the grid should be.

|

1. pport critique sur certaines utilisations abusives de la |

gloup |

est devenu un geste banal plus qu’une décision. |

|

2. que pour beaucoup d’entre nous le fait d’allumer une |

gloup |

. |

|

3. laquelle on est pris pour gens qui “s’abrutissent à la |

gloup |

”, dans une proportion croissante depuis 1896 |

|

4. Tous les grands moments de |

gloup |

superposent un message recherché et un messa |

|

5. sieurs postes et l’augmentation du temps de diffusion ( |

gloup |

du matin et de la nuit). |

|

6.

dailleurs 21% des Français reconnaissent regarder la

|

gloup |

Même si le programme les ennuie. 34% seulem |

|

7. rmettent une plus grande maîtrise individuelle de la |

gloup |

. Les comportements des téléspectateurs en ont é |

|

8. ux Pays-Bas que l’on regarde le moins longtemps la |

gloup |

: 89 minutes par jour, contre 228 en Grande-Bret |

|

9. publications, diffusent des émissions de radio ou de |

gloup |

. Et découvrent les vertus des communications |

Ideas for the creation of handouts in different languages: try similar exercises with words that have dual meanings or different meanings in different varieties of the language. With such words, contexts will contribute strongly to the guesswork required. E.g. English chip or bathroom (in its US meaning), French dépanneur (and its Québécois French meaning), Spanish and Latin American pasaje or manejar, Italian penna or colpito.

Aims of the activity: To raise students’ awareness of stylistic differences between different positions of "donc" in sentences. the placement of "donc" in French in formal written texts compared to informal ones. Ideally, this comparison should be carried out contrasting a written corpus with a corpus of spoken language. However, these are very hard to come by for most languages, so instead we have used two corpora from Corpus Lexicaux Québécois, one of them from an archive of letters written by people with no formal education, in a style very close to spoken French. Many of the words were spelt phonetically in the original and to avoid confusing students we have rectified spelling errors. However, original word order and punctuation have been preserved.

Worksheet: In French you could place a word like "donc" at the very beginning of a sentence, (e.g. "Donc on peut dire que…"). But you often find it between the main verb and what follows the main verb (e.g. "On peut donc dire que…"). Is one better than the other? Where should you put "donc"? To find out, have a look at the two lists below, both from Québec (French Canada). List A is from a set of engineers’ reports about the building of an airport in Inuit territory. List B is from a collection of handwritten letters sent by poor farmers to the authorities (in this case a priest), to ask for financial help. These letter-writers have not studied composition and they write more or less as they speak.

Your job is to look at how many times "donc" is found at the very beginning of sentences and how many times it occurs immediately after the main verb, in each list. When you have done this, draw a conclusion about where you should place "donc" when you write a formal essay, and where you may put it when you are writing (or speaking) in an everyday situation.

List A

|

Il devient |

donc |

difficile de proposer un plan de gestion de ces troupeaux. |

|

u Québec et de tout promoteur développer les terres et |

donc |

, à restreindre les droits des autochtones. |

|

Elle permet |

donc |

la circulation des avions de grandes dimensions en cas de besoin. |

|

Ce droit exclusif n’atténue |

donc |

pas du tout les droits de ces derniers puisque ils ont accès à toutes les |

|

Les autochtones ont |

donc |

priorité quant à la récolte. |

|

Les Inuit ont |

donc |

fait part de leurs points de vue sur l’impact du Complexe ainsi que leur |

|

Il serait |

donc |

intéressant de comparer des données plus récentes afin de |

|

Ces chiffres révèlent |

donc |

une tendance à la baisse entre 1976 et 1980 mais sûrement aussi |

|

Les données furent |

donc |

suggéré de répartir les territoires de chasse selon des zones “ |

|

Ils ont |

donc |

peur de ne pas avoir suffisamment obtenu de terrains pour permettre |

|

L’un des aspects négatifs de la mise en application de |

donc |

de ne pas avoir atteint l’objectif de mettre en place un mécanisme |

|

Il faut |

donc |

déterminer les espèces touchées et leur importance relative |

|

C’est |

donc |

l’épaisseur calculée en fonction du gel qui prime |

|

Ils peuvent |

donc |

théoriquement rencontrer la demande de transport pour les années |

List B

|

l’hiver. Aussi le Père Joseph. Guay aussi ce sont tous des invalides. |

Donc |

je crois qu’il serait à propos de leur donner quelque chose |

|

deux mois, on sait que vous en envoyez et on n’en a pas alors tâchez |

donc |

s’il vous plaît d’être assez bon de nous envoyer à leur nom |

|

le grand besoin avec une famille de 9 enfants ça fait bien dur. |

Donc |

Je compte sur votre secours afin de pouvoir passer l’hiver |

|

bras forts pour envisager les durs travaux qui se rencontrent sur un lot |

Donc |

excusez-nous de vous avoir dérangé dans vos nombreuses occupations. Espérant vous lire sous |

|

garder mes enfants à la maison et les priver de l’instruction. Je compte |

donc |

sur votre grande générosité pour nous tirer d’embarras. |

|

de cet rgent, et depuis longtemps pour financer mes petites affaires. |

Donc |

espérant qu’avec votre concours je recevrai ce petit montant bientôt Je demeure votre tout |

|

seront payés et ceux qui ne travailleront pas n’auront droit à rien |

donc |

il faudra qu’ils travaillent pour avoir de l’aide si non rien. Mais |

|

transport qui m’empêche de finir cette transaction. Je vous serais |

donc |

bien obligé de me dire quels moyens je pourrais prendre pour obtenir un prix réduit |

|

Notre Dame Du Lac Co Témiscouata.Cher Mr Je viens |

donc |

vous écrire pour vous demander si je peux avoir de l’octroi pour racheter ma |

|

le bâtir tout de suite pourvu que je sois certain d’avoir ma prime |

Donc |

je me fie entièrement à vous pour régler cette affaire-là et je vous remercie |

|

année il va être fini mais mais cette année la Compagnie Fraser l’achète. |

Donc |

espérant recevoir une bonne réponse de vous le plus tôt possible. Votre |

|

À autre mais je n’ai pas d’argent et ils demandent déjà un bon prix |

donc |

s’il vous plaît enseignez-moi les moyens à prendre pour le faire annuler et |

|

Bien cordialement. Soyez |

donc |

assez bon de me dire s’il y a encore de bons lots à prendre |

|

Je connais la terre étant fils de cultivateur. |

Donc |

Monsieur le Curé je sais que si vous le voulez je pourrais aller semer |

|

bien si vous pouviez venir inspecter ce chemin |

donc |

je veux pas vous ennuyer avec cela |

Ideas for interactive extension work: If you’re an English speaker, try comparing the work that you have just done on the position of "donc" with the position of its English equivalent "therefore". First, think where you would put "therefore" if you were writing an essay. Use one of the online concordancers and corpora that we list below under Websites to do a free search based on "therefore". What conclusion can you draw about some of the rules of "good" writing in French and in English?

Aim of the activity: to get students to derive (by induction) the rule that "s’agit" never takes any subject other than the impersonal pronoun "il".

Worksheet: "Le roman (or 'le poème' or 'la pièce') s’agit d’un amour malheureux…" When teachers of French read this kind of phrase in students’ essays, they are likely to whip out their red pens and score out the first two words. Why? To answer this, read the following. Then with your group, explain the teachers’ reaction, and decide what precaution you should always take when using the verb "s’agit".

|

1. e de s’adapter au monde contemporain. Il |

s’agit

|

de savoir si l’on table, oui ou non |

|

2. es, de Beurs ni de Blacks (hélas). Il ne |

s’agit

|

pas d’une bande dessinée mais |

|

3. is gaulois. On en use à présent quand il |

s’agit

|

d’évoquer les solutions apportées |

|

4. oins comme ami, simplement parce qu’il |

s’agit

|

de quelqu’un de différent |

|

5. une femme. Et réciproquement. Quand il |

s’agit

|

de cette différence-là il y a |

|

6. olution partiellement dans le prototype. Il |

s’agit

|

de définir les autorisations |

|

7. uation de l’élève faite par le système. Il |

s’agit

|

donc de recueillir ces informa |

|

8. le “welfare State”, l’état-providence, il |

s’agit

|

d’une approche globale et |

|

9. péen Hans van den Broeck, selon lequel il |

s’agit

|

d’”aider” la Grèce à répondre |

|

10. fres et François Maspéro, montrent qu’il |

s’agit

|

bien d’univers distincts, qui |

|

11. meront peut-être certains, pensant qu’il |

s’agit

|

une fois de plus d’un ouvrage |

|

12. virtuel des différends (chapitre VI). Il |

s’agit

|

là d’un ensemble de mesures lo |

|

13. Aucun établissement ne part de rien. Il |

s’agit

|

donc de faire l’inventaire de |

|

14. cours multimédia d’anglais (HELLO). Il |

s’agit

|

d’une réalisation de la BBC en |

|

15. ont représentés. Statutairement, il |

s’agit

|

d’une simple association (type |

|

16. Cela prend énormement de temps. Il ne |

s’agit

|

pas seulement de les lire. Il |

Aim of the activity: To sensitise students to the differences between the English and French false friend "information". Focus their attention on the grammatical differences (with or without an "s") and the way this relates to differences in meaning.

Worksheet: The phrases "some information about the situation" and "une information sur la situation" mean the same. So from this viewpoint, the French word "information" is a good translation for its English counterpart. But if you use a French corpus to search the keyword "information", you will see that this similarity is only part of the story. Do a search using the keyword "information*", adding a wild character as in the example that we have just given, and compare the citations in the singular and in the plural ("informations"). With your group, work out what the difference is between the singular and plural uses of the French word.

|

1. dépourvus: le bon sens. Dans le flot d’ |

informations |

autour du scandale de la |

|

2. nographiques ne fassent aucun travail d’ |

information |

sur les centres et les moy |

|

3. de l’homme de raisonner et de gérer les |

informations |

. Dès lors l’homme informa |

|

4. s optimales les nouvelles techniques d’ |

information |

et de communication”. Au p |

|

5. dias utilisés, la dynamique d’accès à l’ |

information |

, la dynamique d’évolution |

|

6. jout, la modification, la suppression d’ |

information, |

le dictionnaire peut |

|

7. comportement de l’élève. De plus ces |

informations |

peuvent être utiles |

|

8. stème. Il s’agit donc de recueillir ces |

informations |

sous une forme exploit |

|

9. contrôle du praticien. La formation et l’ |

information |

des médecins et de leurs |

|

10. qu’il soit mis un terme à la publication d’ |

informations |

paraissant dépasser le |

Aim of the activity: To sensitise students to the fact that the writings of a culture reflect habits of people of that culture.

Worksheet: In this activity you are going to be asked to compare data, so make sure that you print out each set of results as you progress. Look up "café" using your French concordancer (now print). Then look up "thé" (and print). What conclusions can you draw about French interest in either of these drinks?

Concordance for "café" and "thé"

|

Number

of times |

Number

of times |

|

|

In a Balzac corpus |

99 times |

19 times |

|

In a 1998 corpus made up of a selection of press articles |

14 times |

Zéro! |

Ideas for interactive extension work: Use one of the online concordancers and corpora that we list below under Websites to do the same two searches (this time using "coffee" and "tea"). Print each. Compare the results from these searches with the printed sheets which you obtained earlier. From the evidence, draw some conclusions about each culture’s interest in each of those drinks. Cultural stereotypes and artefacts can be used to great effect (and give a lot of fun) in concordancing.

Aim of the activity: To sensitise students to changes in language use

Worksheet: First read the insert below, which has been adapted from the French dictionary Le Petit Robert, 1984 edition.

anglais, aise: adj. De l’Angleterre (au sens étendu de Grande-Bretagne). Synonyme: Britannique le peuple anglais, la monarchie anglaise, la marine anglaise.

Now look at the following two searches, based on a corpus of texts written in 1998. Compare the lists thrown up by these searches, and the dictionary definitions. How has the French approach to naming their Northern neighbours changed over the last few years of the 20th century?

Anglais, anglaise

|

1. Coutances sur un traffic de 70000 veaux |

anglais

|

touchant la Manche, L’Ain et p |

|

2. quelques rudiments mal digérés de langue |

anglaise

|

), des revues et de l’éplucha |

|

3. naître la langue allemande et la langue |

anglaise

|

, c’est grotesque.” Les pages |

|

4. constante augmentation depuis 10 ans. L’ |

anglais

|

fait un tabac sur les bancs de |

|

5. de jeunes qui ont jeté leur dévolu sur l’ |

anglais

|

dans l’enseignement général, t |

|

6. 87% des collégiens se sont rués vers l’ |

anglais

|

première langue, le plus souve |

|

7. blic (85%) la montée en puissance vers l’ |

anglais

|

première langue, régulière dep |

|

8. Michel Noir souhaite une évolution à l’ |

anglaise

|

et l’adoption du scrutin majori |

|

9. te pilote du nouveau cours multimédia d’ |

anglais

|

Hello). Il s’agit d’une réalisa |

|

10. ses certificates. Elle m’en donna un en |

anglais

|

car elle sortait disait-elle |

Britannique

|

1. ennes et les volte-faces du gouvernement |

britannique

|

leur paraissait bien lointaines |

|

2. sociaux douloureux. Le premier minister |

britannique

|

, M. John Major, en sait quelque |

|

3. En revanche, rassuré les investisseurs |

britanniques

|

et la politique de relance |

|

4. Aux échéances électorales les brokers |

britanniques

|

n’hésitaient pas miser sur |

|

5. ntrôle de la Midland, quatrième banque |

britannique

|

. La HSBC emportait finalement |

|

6. r. les vives attaques contre la monnaie |

britanniques

|

. Le 16 septembre, la solida |

|

7. juguée à une baisse des taux |

britannique

|

à moins de 10% pour la première |

|

8. affaire personnelle, que la présidence |

britannique

|

? Et si leurs dirigeants avaient |

|

9. ratification du traité par le Parlement |

britannique

|

a tellement influé au cours des |

|

10. é. Face à une crise qui mine l’économie |

britannique

|

les réponses ne sont pas toujours |

Both sub-activities in this category look at language as it changes. The first one is easier, and involves a simple comparison of two KWIC concordances. The second one is more demanding, and combines linguistic analysis of a concordance with critical reading of an entry in a dictionary.

Aim of activity: to introduce students to the idea that a corpus reflects the society of its time. Also, to raise their awareness that the result of a concordance search is highly dependent on what was in the corpus in the first place.

Worksheet: work out the meaning of the word "mail" in each row of each of the grids below, by guessing from the context if necessary. List A is taken from selected works of Balzac (1799-1850). List B is from several issues of the French weekly magazine L’Express, published in January 2000. What conclusions can you draw about how to choose texts for use in the kind of vocabulary research that you are doing at the moment?

Balzac

|

S’il

existe en province un

|

mail

|

, un plan, une promenade d’où se |

|

hier avait

été convertie en un

|

mail

|

, ombragé d’ormes sous lesquels |

|

par les

beaux temps sur le

|

mail

|

qui enveloppe la ville du côté de |

|

vu promenant

sa chienne sur le

|

mail

|

, répondit le curé. Ah ! notre |

|

jambes de

héron au soleil, au

|

mail

|

, regardant la mer ou les ébats de |

|

Guérande,

et se promena sur le

|

mail

|

, où il continua sa délibération |

|

Calyste

aperçut de loin sur le

|

mail

|

le chevalier du Halga qui se |

|

fille, se

croyant seuls sur le

|

mail

|

, y parlaient à haute voix . |

|

intelligence

J’étais sur le

|

mail

|

quand Mlle de Pen-Hoël parlait à |

|

promenait

sa chienne sur le

|

mail

|

, la baronne, sûre de l’y |

L’Express

|

is on transmet

l’annonce par e-

|

mail

|

au site, qui la publie gratuitement: |

|

e la repression

en Iran. Voici le

|

mail

|

(en anglais) d’une etudiante iranie |

|

autres rubriques

habituelles: météo,

|

mail

|

, chat ainsi que des fonctions d’ag. |

|

envoyait

une copie de son adresse e-

|

mail

|

privée et le descriptif de son matériel |

|

exion, pour

l’envoi et la réception de

|

mail

|

en direct. Des versions de cette boîte |

|

l’ordinateur

pour les envoyer par

|

mail

|

à un ami inculte. Rien n’empêche, n |

|

60, cette

fête se tenait sur un grand

|

mail

|

jalonné de platanes vieux comme Du |

|

plus grand

utilité pour recevoir un

|

mail

|

, consulter son agenda ou surfer sur |

|

de signer

sa dernière création, E-

|

mail

|

, utilisant Internet pour délivrer un |

|

ainsi le

quotidien britannique Daily

|

Mail

|

vient-il de consacrer sa première |

Aim of the activity: This activity takes its starting point in obvious similarities between two languages - in this case English and German. The activity ought to show the student that in German one can’t say: Du musst nicht! The following worksheet was made on the basis of KWIC-concordances of darf, dürfen, müssen.

Worksheet: dürfen and müssen

|

In English it is (grammatically!) acceptable to say:

Of course the meanings of these two sentences are different, but that is another story. In German the meaning of dürfen resembles that of may in English and must that of müssen. Is that really true? A. Study these examples of the use of dürfen and müssen in German:

...............Wer ist dein Vater? Das darf ich nicht sagen. Was

brummst ... .........warum

haben Sie denn fahren müssen? Ach was! sagte Karl und ... B. Fill in the correct verb in the correct form: ....................Sie das? Ich nicht. Das _____________ Sie sich nicht gefallen lassen, ... ...............Sorgen zu haben. Aber es _____________ die Folgen meiner früheren Sorgen ... ......faulen und gefrässigen Robinson _____________ du dir kein Beispiel nehmen ... C. State the rule. To express disallowance in German you use:

______________________________________________________________________ |

The use of prepositions is a concordancer’s darling. Often a corpus will give a lot of output and though their collocations in different languages are somewhat similar they also differ quite a lot.

Aim of the activity: In the following output from a 50,000 word corpus of L. Tieck’s writings the idea is simply to answer the question by looking through the examples. We have done some editing of the output (but only to some extent) in order to give an example of a relatively “raw” output from a concordancer.

Worksheet: The use of am as a preposition of time in German

| Look

through the following KWIC-concordance of am and decide in which

cases it is used as a preposition of time:

.......einem

Gemache des Hauses bis am Morgen zu schlafen. Walther ging ... |

Aim of the activity: this activity relies heavily on a statistical evaluation of the output. It took quite a while to figure out what corpus to use and what search words to use. In this case the activity makes use of an online corpus, but such exercises can equally well - or perhaps better - be done interactively with a corpus of a moderate size. If you do not narrow down your search, you may well obtain too much information to make it possible to draw a conclusion.

Worksheet: Syntax of adverbs

|

Open your browser and select one of the online concordancers and corpora that we list below under Websites. Exercise A Search for “never+should”. How many hits did you get? ______________ Try other combinations, such as “never+would”, “never+should”, “never+could”, “always+could” etc. and note how many hits you get. Write down some of the citations here: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Exercise B Now reverse the order. Search for “could+never” etc. How many hits? _________ As for the word order of small adverbs of frequency and modals, the conclusion is that _______________ usually precedes ______________________. Look at the examples you noted in Exercise A. Think of reasons why the author(s) used that position of the adverb of frequency. Write them here: __________________________________________________________________ Exercise C Use the same method to discover the position of adverbs of frequency in compound verbs. e.g. Never+has/has+never/always+could etc. And now think about the answer to this question: is there a difference between UK and US usage? |

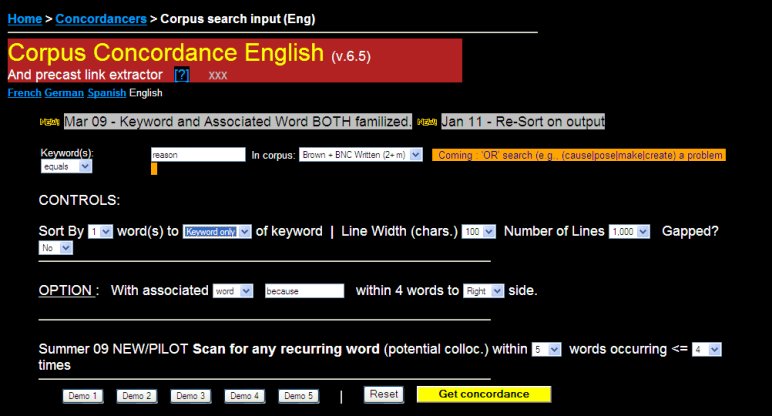

Aim of the activity: Correctness is often an issue with foreign language students. In this case online corpora can be used simply as a reference source. The sample also shows how the browser’s search function can be used. The corpus that is used here is fairly small which makes the outcome slightly more predictable. Furthermore: The idea is that the number of occurrences of “reason + because” is relatively small so the conclusion could be that though it does occur it is not a use that should be recommended.

Worksheet: reason + because

| Question: How acceptable is a construction like this: |

| The reason is because he didn’t want to harm her? |

| Answer: |

|