ICT4LT

Module 2.2

ICT4LT

Module 2.2 ICT4LT

Module 2.2

ICT4LT

Module 2.2

This module aims to provide the newcomer to multimedia CALL with the knowledge he/she needs in order to make informed decisions about multimedia hardware and software. This module consists of three main sections:

This Web page is designed to be read from the printed page. Use File / Print in your browser to produce a printed copy. After you have digested the contents of the printed copy, come back to the onscreen version to follow up the hyperlinks.

Graham Davies, Editor-in-Chief, ICT4LT Website.

The term multimedia was originally used to describe packages of learning materials that consisted of a book, a couple of audiocassettes and a videocassette. Such packages are still available, but the preferred terms to describe them seem to be multiple media or mixed media - although there is considerable disagreement as to what they should be called now that the term multimedia has acquired a different sense. Nowadays multimedia refers to computer-based materials designed to be used on a computer that can display and print text and high-quality graphics, play pre-recorded audio and video material, and create new audio and video recordings. Because of its capability of integrating the four basic skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing, multimedia is of considerable interest to the language teacher.

The first popular microcomputers that appeared in the 1970s were incapable of playing or recording sound and video, and they had very limited graphics capabilities. Language teachers were often critical about CALL because it lacked the essential ingredient of sound. From the early 1980s various tricks were employed to get computers to play back authentic sound, for example linking an audiocassette player to a computer that controlled the playback and rewind functions - but this was not very efficient as the tape stretched with use and bits of audio were cut off or appeared in the wrong place. All sorts of other Heath-Robinson devices were invented by inspired CALL enthusiasts in order to get computers to produce high-quality authentic sound. The videodisc player appeared in the early 1980s, offering the possibility of playing back high-quality sound and video and presenting thousands of photographic-quality pictures. The 12-inch videodiscs (or laserdiscs as they were sometimes called) could hold around 30 minutes of video or 54,000 still images on each side. By linking a videodisc player to a computer it was possible to produce CALL programs that today would be described as multimedia. In those days, however, the term interactive video was used.

One of the best interactive videodiscs ever produced is MIT's A la rencontre de Philippe, which wraps up language learning in a real-life simulation set in Paris. Philippe is a freelance journalist from the provinces currently living in Paris with his girlfriend, but in the first scene she dismisses him and the learner has to find an apartment for Philippe, reconcile Philippe with the girlfriend, and help Philippe get a better job. A plan of Paris with clickable street names and a notebook are provided, and the learner has access to a telephone, Philippe's answering machine, classified ads, and list of accommodation agencies. The learner can telephone to find information about different apartments and look around them, and follow story lines in which various characters (e.g. a plumber, an aunt, a best friend) appear. At various points in the story, Philippe will ask the learner a question and the next segment depends on what the player answers: e.g. if the learner clicks on "Your boss called" a different storyline will be engaged than if the learner says "I found you a great apartment". The material, at least the video portions and many of the stills, was filmed in Paris. The learner can read a description of the scene or review its essential bits before watching it, but must watch from beginning to end before being able to access a transcript or selective review. The transcripts include clickable glossary words and notes on idiomatic phrases. There are also encouraging reminders of what the player should be doing in a given situation, and review tests to check that the learner has absorbed the essential information of a scene. See Fuerstenberg (1993).

Other examples of simulations on videodisc are Montevidisco, in which the learner is cast in the role of a tourist in a fictitious town and must interact with salesmen, waitresses, policemen and other inhabitants (Schneider & Bennion 1984), and EXPODISC, which casts the learner in the role of assistant to the export manager of a company wishing to sell its products in Spain and Latin America (Davies (1991). See Section 5.10, Module 3.2, headed Branching dialogues.

It's a great pity that simulations like these have not really caught on among CD-ROM developers - with one notable exception: the Who is Oscar Lake? series, which is described below in Section 3.4.9, below.

Interactive videodiscs continued to be used in industrial training well into the 1990s - and also for karaoke entertainment. Their main advantage was the high quality of the sound, video and still images that they could produce, which is absolutely essential, for example, in training engineers how to assemble a mechanical device - a typical application of the time. Their main disadvantage was the high cost of the equipment required to run them - and it was messy too, consisting of several different components linked with lots of cables.

The multimedia computer (MPC) was the next major landmark in the history of multimedia, appearing in the early 1990s. The MPC was a breakthrough in terms of its compactness, price and user-friendliness. Most PCs that are currently available can be classified as multimedia computers. These following components are essential features of an MPC:

These components are discussed in more detail in Section 2 below. See also Module 1.2 for more information about computer hardware.

There were earlier computers that qualified as multimedia computers, e.g. the Apple Mac and the Acorn Archimedes in the UK, but the dominant multimedia computer is the MPC. Apple computers appear to have a commanding position in the print and graphic design industries, while Acorn computers only ever gained a foothold in the UK schools sector and finally lost their market share to the MPC.

Now we have multimedia on the Web. It's a growing area but it has not completely supplanted CD-ROM or DVD technology. For example, we are still waiting for the Web to deliver listen / respond / playback activities that compare favourably with those offered by the first AAC tape recorders in the 1960s. CD-ROMs were able to deliver such activities as far back as the late 1980s. Such CD-ROMs are still produced by EuroTalk.

See the following modules:

It is evident from the number of visits to this module - the most frequently visited module at the ICT4LT website - that there is an enormous demand for information on multimedia and for INSET training courses. Section 2.2.3, Doing it youself, (below) contains information on some of the tools that you can use to create your own multimedia materials.

Contents of Section 2

Certain minimum hardware specifications are desirable if you intend to run multimedia applications on a computer. Modern computers are normally equipped with the following essential components as standard:

The computer must also have a recent version of the Microsoft Windows operating system installed: see Section 2.1, Module 1.2.

If the application you wish to use is on the Web then you will probably find a reference to the speed of the Internet connection that you need to have. This is dealt with in Module 1.2, Section 1.3.2, headed Modem

An adequate soundcard is essential for multimedia. Modern multimedia computers are fitted with soundcards as standard, so the choice of soundcard may already have been made for you. You should familarise yourself with soundcard controls under the Windows operating system that enable you to adjust the output volume of your soundcard and the input sensitivity of your microphone. For further information see Section 1.2.2, Module 1.2.

Speakers or headphones are essential for listening to sound recordings. When purchasing speakers it is worthwhile checking that they have their own inbuilt amplification system. The sound level of all speakers or headphones can be controlled under the Windows operating system, but good speakers have a volume control knob that also enables the user to adjust the volume manually. Headphones can be integrated with a microphone - the so-called pilot's headset that is used in language laboratories. Stereo speakers or headphones are advisable for most multimedia applications. See also Section 1.2.3, Module 1.2, which contains an illustration of the pilot's headset.

The importance of selecting the right kind of microphone is often not appreciated by ICT technicians. For good quality sound recordings the language teacher needs a high-quality microphone. A dynamic microphone (also known as a karaoke microphone) is satisfactory but provides a softer signal than a condenser microphone (also known as a powered microphone).

The level of the input signal to the microphone can be controlled under the Windows operating system. A common mistake made by newcomers to multimedia applications is a failure to set the input signal control properly so that very faint sound - or no sound at all - is emitted when playing back recordings made by the user.

A microphone can be integrated with headphones - the so-called pilot's headset that is used in language laboratories. See Section 1.2.4, Module 1.2.

The term card in this context is jargon for an electronic circuit board. You will not be able to see the graphics card from outside the computer. All that is visible is the rear of the card is the socket into which you plug the monitor. It is important to know what kind of graphics card your computer is equipped with, as this affects what the monitor can display, i.e. the quality or resolution of its output. When you purchase software make sure that your computer has a graphics card that is compatible with the software you wish to use. Some software, e.g. computer games, will only work on computers equipped with cards with high specifications.

Graphics cards control the resolution of the text, pictures and video that appear on the screen. The resolution is determined by the number of small discrete dots, technically known as pixels (see Glossary under the entry Pixel), that make up the picture on your screen and therefore its definition or clarity. CALL software often requires a card that can display colour photographs and movies. It is therefore important that your graphics card can display a large number of different colours. You may need to adjust the resolution of what is displayed on your computer screen. Most modern graphics cards are accompanied by software that enables you to control the resolution of the display screen according to the software that you are using. You may need to vary the resolution according to the software you wish to use. For example, you may need to set the resolution to one of the following settings:

The lower the numbers, the lower the resolution. A 640 x 480 setting offers a "chunky" appearance. 800 x 600 and 1024 x 768 are fairly "safe" general settings for most software. Getting the graphics card setting wrong is one of the commonest reasons for failing to get software to work properly. This is normally done using the Windows Control Panel on your computer. If you are unsure about how to do this, consult your ICT manager.

Modern computers are now usually equipped with a combination drive that enables both CD-ROMs and DVDs to be played and recorded, as well as playing and recording audio CDs. CD-ROM stands for Compact Disc Read Only Memory. A CD-ROM is an optical disc on to which data has been written via a laser - a process often referred to as burning a CD. A CD-ROM looks much the same as an audio CD but can contain text, sound, pictures and motion video. Once written, the data on a CD-ROM can be fixed and rendered unalterable, hence the term Read Only - but most modern computers are usually equipped with a read/write drive that enables new material to be stored on a recordable CD-ROM (CD-R) or rewriteable CD-ROM (CD-RW). Blank CD-Rs or CD-RWs can be bought from computer media suppliers at a relatively low cost. You can store data on CD-Rs using a read/write drive, adding to it until it is full, and then you can format the CD-ROM so that it is fixed and can be read by a standard CD-ROM drive. You can also store data on CD-RWs in the same way, but these discs can only be read by a CD read/write drive. The advantage of CD-RWs is that they can be erased and used over and over again, but now that the cost of blank CD-Rs has fallen to such a low level it is questionable how useful CD-RWs are.

CD-ROMs can store at least 650 megabytes of data. A single CD-ROM can comfortably accommodate 500 medium-length novels, a 12-volume encyclopaedia, the complete works of Shakespeare, a whole year's edition of a newspaper, hundreds of your favourite photos, or a high-quality 30-minute movie.

A CD-ROM drive can also play standard audio CDs, so you can listen to your favourite music while you work or follow a language course supplied on audio CD - but most computer technicians keep quiet about this as they don't want their computer lab turning into a discotheque or language lab! It is possible to extract or copy tracks from an audio CD and save them to your computer's hard disc as audio files, which can then be played, edited, written back to another CD, or saved to an iPod or similar mobile player. This process is often referred to as ripping a CD.

CD-ROM and DVD drives are slow compared to hard disc drives. They are available in a variety of different speeds, the speed being described thus: 12x (12-times), 24x (24-times) - and much faster speeds nowadays. This indicates the speed at which data can be pulled off the CD-ROM drive, the so-called spin-rate, with 150 kilobytes per second being the notional original 1x spin-rate - long since superseded. A high spin-rate helps speed up data transfer, which is crucial when playing sound or video. A low spin-rate may cause hiccups when audio and video recordings are played. CD-ROMs and DVDs normally work fine on stand-alone computers but networking them, especially if they contain large amounts of sound and video, can be problematic. Although it is technically possible for a limited number of network users to access data on the same CD-ROM or DVD, the success of this depends on a number of technical factors that are too complex to discuss here, and you are therefore advised to consult your network manager. See also the Appendix: Networking CD-ROMs and DVDs.

Compared to the older 12-inch videodiscs (see Section 1.2 above), the first CD-ROMs produced poor quality video, but this obstacle has now been overcome. It is ironic that the early CD-ROM technology represented a major step backwards in terms of the quality of the video it offered, and it is surprising that it was tolerated for so long. Perhaps it was a case of newcomers to CALL not knowing any better. Now, with the advent of DVDs, we have caught up with what was available in the early 1980s. More on DVDs below in Section 2.1.7.

Multimedia CD-ROMs were designed mainly for use on stand-alone computers. This is because the main target of CD-ROM manufacturers is the home user. This is not to say that CD-ROMs have no place in schools and other educational institutions; the main problems are technical and organisational. It was not until around 1993-94 that multimedia CD-ROMs for language learning began to appear in large numbers. David Eastment was quick to identify the problems associated with early CD-ROMs:

It is difficult to see how CD-ROM could be used effectively in a conventional Computer Room. Networking CD-ROMs is fine for simple text. But sending video and audio information around the net so that it finishes up perfectly synchronised at each user's workstation is fraught with difficulties. The alternative is to set up each of the student stations as multimedia machines with their own CD-ROM drives, and provide each station with the CD-ROM discs it needs. It is problematic enough working like this from floppy disc, where at least you can copy the information on to multiple copies and keep your master safe. Working with CD means that every single workstation would have to have its own original CD-ROM disc in place, Frankly, I cannot imagine many schools going down this path. Soon, perhaps, the technical problems will be solved, or new software will emerge which will prove more "classroom-friendly". For the moment, however, CD-ROM is likely to be confined either to individuals or to small groups at a single PC. (Eastment 1994:75)

The technical situation has improved considerably since these early times. The problems identified by David Eastment have largely been overcome, but there are still a number of factors that need to be taken into consideration if you wish to run a CD-ROM on a network: see the Appendix: Networking CD-ROMs and DVDs.

See also Section 1.2.1, Module 1.2.

Modern computers are now usually equipped with a combination drive that enables both DVDs and CD-ROMs to be played and recorded, as well as playing and recording audio CDs. DVDs (Digital Video Discs), also known as Digital Versatile Discs, look just the same as CD-ROMs (see Section 2.1.6 above) and audio CDs, but they are much more versatile and can store much more data. They are already in widespread use to store movies that can be played back on domestic TV sets via a DVD player. DVDs can also be used to store computer data, which can be read by a computer equipped with a DVD drive.

Modern multimedia computers usually come equipped with a DVD read/write drive or a combination drive that can read and write to DVDs and CD-ROMs, as well as playing and creating audio CDs.

First, an important distinction:

The main advantage of all types of DVDs is that they offer very high quality video and sound. In this respect they have caught up with - and surpassed - the video quality offered by older 12-inch videodiscs: see Section 1.2. Their capacity is impressive - up to 25 times the storage capacity of a CD-ROM, which means that a DVD can comfortably hold a full-length movie. Most modern computers can play DVD-Video discs and DVD-ROM discs.

See also Section 1.2.1, Module 1.2.

Standards for DVD-Video are still in the process of settling down. An annoying aspect of DVD-Video is that the world is carved up into six regions, also called locales, each of which has its own DVD standard. DVD-Video discs are regionally coded - look for a small standardised globe icon on the packaging with the region number superimposed on it. If a disc plays in more than one region it will have more than one number on the globe. The current six regions are:

1. USA, Canada

2. Western Europe, Japan, South Africa

3. South East Asia

4. Australia, Spanish America

5. Russia, Eastern Europe, Africa

6. China

A DVD-Video disc coded for Region 1 (USA, Canada) will not play on a DVD player sold in Region 2 (Western Europe, Japan, South Africa). When you buy a computer equipped with a DVD drive, the region will have been pre-set, but you can change it via Windows. The problem is that you cannot keep doing this: you normally only have five chances (more on some systems) to change regions! There are various reasons for this non-standardisation, one of them being that movie producers release movies at different times in different regions and in different variations. There are various ways of getting round the problem of non-standardisation - but this is beyond the scope of this introduction and you are advised to consult someone who is technically competent in this area.

DVD-Video discs have impressive advantages. You can play back a full movie with 8-channel surround-sound cinema effects. You can easily jump to a particular sequence (a scene or chapter), and DVD-Video discs often offer alternative soundtracks in different languages, subtitles (i.e. subtitles in a language other than the one in which the film was recorded), closed captions (i.e. subtitles in the same language as the one in which the film was recorded), and information about the director and cast, as well as the possibility of previewing and playing your favourite scenes over and over again.

DVD-ROM discs are not subject to the same geographical restrictions as DVD-Video discs. They only run on computers equipped with a DVD drive and cannot be played on a domestic DVD player - but, having said that, DVD technology is in the process of settling down and moving towards fully integrated systems. DVD-ROM discs combine computer programs and movies and are becoming increasingly flexible as an instructional medium, especially for Modern Foreign Languages. There is a good series of DVD-ROM discs produced by EuroTalk under the name Movie Talk. The series is aimed at advanced language learners and is based on authentic movies of between 50 minutes and 112 minutes in length - each complete movie being stored on the DVD. The complete series consists of:

Each DVD is divided into six sections:

Video & Script: The whole movie can be viewed in full-screen mode without subtitles or in small-screen mode with subtitles and an optional rolling script. If the learner wishes to view a particular scene and play it over and over again, it can be selected from a menu.

Movie Quiz: The learner takes part in a quiz on the movie, pitting his/her wits against a "virtual" competitor - a character who has already appeared in another EuroTalk series.

Record Yourself: The learner can choose a character in a short clip from the movie and record his/her own voice, which is then substituted for the character's voice.

Dictionary: The learner can look up a word, which is then spoken aloud and illustrated with a still picture from the movie.

Word Search: The learner can look for an example of a word in use. A short clip containing the word will then play.

Activities: These consist of a four types of interactive exercises:

In addition, it is possible for the learner to select his/her support language, e.g. a Spanish MT speaker learning French could select Spanish as the support language. Individual learners' names are stored, with a record of their score, the date on which they last used the DVD, and the total number of sessions in which they have used it.

Further information can be obtained from EuroTalk.

Screenshot: Movie Talk French: "Au coeur de la loi"

The EuroTalk DVDs are on the whole well designed and a good illustration of the kind of interaction that is possible with this new medium. The quality of the video in particular is a huge step forward from the poor quality video that characterised early CD-ROMs.

Multimedia and Digital Commentary Online, a website maintained by Mike Bush at Brigham Young University: http://moliere.byu.edu/digital/ - contains lots of useful information and many links to other sources.

A scanner is a device that copies hard copy information (printed page, graphic image, photograph etc) into digital data, translating the information into a form a computer can store as a file. Thus it is possible to make a digitised copy of a printed page, graphic image or photograph. Simple graphic images are usually stored in a format known as GIF. Photographs are usually stored in a file format known as JPEG or JPG and they can then be printed on a colour printer, sent as an email attachment to a friend or colleague, or incorporated into a website. All the images at the ICT4LT website are stored in JPEG or GIF format. See Section 2.2.3.1, headed Image editing software.

Scanners do not distinguish text from graphic images and photographs, so you cannot use a word-processor to edit directly a printed page that has been scanned. To edit text read by an optical scanner, you need optical character recognition (OCR ) software to translate the image into 'real text', i.e. a format that can be read by a word-processor. Most optical scanners today come bundled with OCR software: see Section 2.2.3.2 below.

The most popular type of scanner is known as a flatbed scanner. This looks a bit like a photocopier and works in a similar way. You lay the picture or page containing the text to be scanned on a glass plate, start the scanning software and watch the digitised image appear on screen. The image can then be saved as a file on your hard disc. Text saved as an image can then be converted into "real text" with the aid of OCR software. OCR software does not work 100%, as broken characters and faded characters are liable to be misread, but surprisingly good results can be achieved - and it certainly beats typing!

Some scanners are small hand-held devices that you slide across the paper containing the text or image to be copied. Hand-held scanners are fine for small pictures and photos, but they are difficult to use if you need to scan an entire page of text or larger images.

Software that you require for running multimedia applications is normally supplied with your multimedia computer. A media player is in effect a virtual playback machine, complete with Play, Stop, Pause, Fast Forward, Fast Reverse and Volume Control buttons. Media players installed on your computer can also act as a plug-in when an audio or video clip is accessed on the Web. A media player should automatically spring into action when your computer needs to play an audio or video clip on the Web. Examples of media players include:

Windows Media Player: Normally bundled with the Windows operating system.

VLC Media Player: A cross-platform (PC and Mac) media player that plays virtually any type of media file.

iTunes is used mainly for playing and organising multimedia files and transferring them to an iPod or similar mobile devices. iTunes also offers an extensive online library of music recordings and video recordings. The Open University in the UK has made some of its language-learning materials available via iTunes and is reporting a huge uptake. See Section 5, Module 2.3 on Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL).

Other media players may also be required to play videos and animations on Web pages, e.g. Flash Player, QuickTime, Shockwave Player or RealPlayer.

CODEC is short for COmpressor / DECompressor or COder / DECoder. A CODEC is software that is used to compress or decompress a digital audio or video file. CODECs are additional pieces of software that operate in conjunction with different media players, and certain types of audio and video recordings will only play back if the relevant CODEC is running in conjunction with the media player that you are using.

A CODEC can consists of two components, an encoder and a decoder. The encoder compresses the file during creation, and the decoder decompresses the file when it is played back. Some CODECs include both components, while other CODECs include only one. CODECs are used because a compressed file takes up less storage space on your computer or on the Web.

When you play an audio or video file in your media player it will use a CODEC to decompress the file. Remember that the extension WAV, MP3, AVI, WMA, WMV or MPEG is not a guarantee that an audio or video file can be played in your media player, as the file may have been compressed using a CODEC that is different from those already installed on your computer.

If you have a problem playing an audio or video file in your media player it is likely that the CODEC required to play it is not installed on your computer. Sometimes when you are trying to play an audio or video file an "Unexpected File Format" message or a similar error message pops up - or you may hear the sound without the video being displayed. To correct such problems you need to download and install the correct CODEC. This may be a job for your technician! See:

Digital language labs incorporate a media player/recorder, but go one step further insofar as they offer, in digital format, the same kind of audio-interactive facilities found in a traditional language lab, including teacher monitoring facilities and video playback. See Davies, Bangs, Frisby & Walton (2005 - regularly updated) for a comprehensive discussion of the pros and cons of using digital labs, different types of digital labs and the questions you should ask if you are considering the purchase of a digital lab. See also the case studies in Module 3.1. The following businesses supply digital language labs:

Tecnilab Group, Multimedia Labs: http://www.tecnilab.com/pagine/en/mainlab.lasso

Most modern computers are equipped with a DVD drive or a combination CD-ROM/DVD drive. It is likely that your computer will have a DVD media player pre-installed if you have purchased a computer with a DVD drive. But many other media players will also play DVDs - see Section 2.2.1.

Have a look at Module 2.5, Introduction to CALL authoring programs, which is an introduction to producing your own interactive materials. If you intend to develop multimedia applications you will need additional editing software to create and edit images, audio files and video files - collectively known as assets. A selection of packages for creating and editing images, sound and video is described below.

2.2.3.1 Image editing software

See the JISC Digital Media website for advice creating, managing and using still image resources.

When using the above packages, it is important that you are aware of the different formats in which images can be stored on a computer. Most image editing packages allow you to save images in different formats and to convert from one format to another. The commonest formats are:

BMP: Bitmap format. This is the standard format used by Windows Paint. Images stored in this format tend to be rather large, however.

EPS: Encapsulated Postscript format. An image file format that is used mainly for printing images on Postscript printers.

GIF: Graphic Interchange Format. This format is commonly used for storing simple graphics on the World Wide Web, e.g. line drawings and maps. GIF files use a palette of 256 colours, which makes them practical for almost all graphics except photographs. Generally, GIF files should be used for logos, line drawings, icons, etc, i.e. images that don't contain a rich range of colours. A GIF file containing a small number of colours tends to be small, but it will be big if the image has a wide range of colours, e.g. a photograph. GIF files are commonly used for storing images on the Web. GIF files are also suitable for storing animated images.

JPG (or JPEG): Joint Photographic Expert Group format. The JPEG/JPG format uses a palette of millions of colours and is primarily intended for photographic images. The internal compression algorithm of the JPEG/JPG format, unlike the GIF format, actually throws out superfluous information, which is why JPEG/JPG files containing photographic images end up smaller than GIF files containing photographic images. If you store an image, say, of a flag containing just three colours in JPEG/JPG format it may end up bigger than a GIF file containing the same image, but not necessarily a lot bigger - it depends on the type and range of colours it contains. JPEG/JPG files containing photographic images are normally smaller than GIF files containing photographic images. JPEG/JPG files are commonly used for storing images on the Web.

TIFF or TIF: Tag Image File Format. Files stored in this format give a high-quality image but they are huge!

2.2.3.2 Scanning and OCR software

Most image editing packages also include software for acquiring images from scanners: see Section 2.1.8 above. When you buy a flatbed scanner it is normally supplied with software for scanning images from photographs or other printed media, and with optical character recognition (OCR) software for scanning in texts and converting them into a format that can be read with a word-processor and then edited. See OmniPage at http://www.nuance.com

2.2.3.3 Sound recording and editing software

See the JISC Digital Media website for advice on creating, managing and using audio resources.

(i) Software for making and editing sound recordings

Making and editing sound recordings is not as difficult as many language teachers imagine. These are some of the software packages available for making sound recordings:

Adobe Audition: The "industry standard", the successor to Cool Edit.

Audacity: An excellent free software package that offers all the essential features of recording and editing. The basic software saves files in WAV format (see below), but you can download additional (free) software, the LAME MP3 Encoder in order to create MP3 files. See the Audacity tutorial by Joe Dale at the CILT website. Joe Dale's blog contains many references to audio recording using Audacity: see the thread Using audio creatively in the MFL classroom.

GoldWave: http://www.goldwave.com/

NCH Software: A wide range of useful audio tools, including some downloadable freeware: http://www.nch.com.au/

Sound Recorder - supplied with Windows. Rather primitive, with only basic operations. Suitable only for introducing language teachers to audio recording and editing.

It's easy to make recordings directly onto the hard disc of your computer using one of the above packages, but I prefer to make them first on a portable recorder and then upload them to the computer using a connection lead. There is a range of portable recorders offered by Olympus http://www.olympus.co.uk/voice/

You might also consider using a USB Voice Recorder, which is a small device that enables you to make your recordings while on the move, and you can then upload them to your computer's hard disc via a USB port - see the illustration of a USB port in Section 2.2.3.4.

Once you have made your recordings and stored them on the hard disc of your computer you can copy them into iTunes and then onto your iPod. You can also copy selected recordings onto CD-ROM or onto audio CD using Windows Media Player. See:

How to Burn a Music CD Using

Windows Media Player 9:

http://www.wikihow.com/Burn-a-Music-CD-Using-Windows-Media-Player-9

...and, of course, this works for any kind of recordings, including voice recordings.

Later versions of Windows Media Player make this task very straightforward.

See the next section on Video editing software. Some video file formats can be used both for audio and for video.

(ii) Podcasts

After you have created your recordings you may want to broadcast them as podcasts on the Web: see Section 2.2.3.5 (below).

When using the above software packages, it is important that you are aware of the range of formats in which sound can be stored on a computer. Most sound editing packages allow you to save images in different formats and to convert from one format to another. The commonest formats are:

MP3: The standard format for storing sound files, especially music, on the Web. MP3 is the form favoured for podcasts. The advantage of this format is that it compresses the sound, thereby saving space, without a significant loss in quality. MP3 is a variant of MPEG: see Section 2.2.3.4 below.

MP4 AAC: Abbreviation for MPEG-4 Advanced Audio Coding. The MP4 AAC file format is used to store audio files in a more manageable size without affecting the quality. MP4 AAC's best known use is as the default audio format of Apple's iPhone, iPod and iTunes media player. See also the reference to MPEG-4 Advanced Video Encoding, below.

WAV: Until recently, the commonest format. Produces high-quality sound but takes up quite a lot of space.

WMA: Windows Media Audio is Microsoft's own audio encoding format which offers high-quality output with lower file sizes.

(iii) Transferring recordings from one format to another

These pages at the WikiHow website are useful sources of information on

How to transfer cassette

tape to computer

http://www.wikihow.com/Transfer-Cassette-Tape-to-Computer

2.2.3.4 Video editing software

See the JISC Digital Media website for advice on creating, managing and using moving image resources.

If you have made video recordings using a camcorder these can be uploaded to your computer. There are two basic ways of doing this: (i) via a USB cable and a USB port on your computer, (ii) via a fireware cable and a firewire port on your computer. A port is a technical word for a socket. You upload what you have recorded and edit it using software such as Windows Movie Maker or one of the other video uploading/editing packages listed below.

All modern computers have at least one USB port, but a firewire port is not yet standard. If your computer does not have a firewire port then you have to buy a firewire card and slot it in - and here you need a bit of technical knowledge. If you are not sure that you have a firewire port, have a look at the sockets for connecting to external devices on your computer. A firewire port is smaller than a USB port, but it will probably be located near the USB port(s): see the images below. The advantage of using a fireware port is that it offers a much faster transfer speed from your camcorder to your computer. If you have a large movie clip to upload then it will take an eternity if you use a USB port.

|

|

|

|

|

Firewire

port

|

Firewire port (left) |

Firewire

cable

|

USB cable

|

Most popular camcorders are able to make video recordings that can easily be uploaded to a computer. Many are provided with software that helps you upload and edit video recordings. The author of this module, Graham Davies, uses a Sony Handycam. Two videoclips made with this camera, which were edited using Windows Movie Maker, can be viewed here:

There are many good video editing packages that enable you to upload and edit video recordings:

TV broadcasts are another source of learning materials, especially satellite TV broadcasts, which offer a wide range of materials in foreign languages. TV broadcasts can also be uploaded to your computer but beware of the copyright restrictions relating to the use of publicly broadcast audio and video materials: see Section 6 in our General guidelines on copyright. There is a good range of products offered by Hauppauge for the efficient digitisation of video materials from a variety of sources http://www.hauppauge.com/.

It is important that you are aware of the different formats in which video can be stored on a computer. Most video editing packages allow you to save images in different formats and to convert from one format to another. The commonest formats are:

ASF: Advanced Streaming Format. This is a Microsoft's own file format that stores both audio and video information and is specially designed to run over the Internet. ASF enables content to be delivered as a continuous stream of data (streaming audio or streaming video) with little wait time before playback begins. This means that you no longer have to wait for your audio and video files to fully download before starting to view them. Cf. the WMV format (below).

AVI: Audio Video Interleave format. Still very popular, but giving way to MPEG, which takes up less storage space.

FLV: Abbreviation for Flash Video, a proprietary file format used to deliver video over the Web using the Adobe Flash Player plug-in. See FLV.com.

MOV: The standard format for storing video files on the Apple Macintosh to be played in the QuickTime media player - which is also available for the multimedia PC. Economical in terms of storage space. See http://www.apple.com/quicktime/

MPG or MPEG: Motion Picture Expert Group. Probably the commonest format for storing video, especially on the Web. Economical in terms of storage space. See http://www.mpeg.org/, a reference site for MPEG, with explanations of different MPEG formats and links to sources of media players.

MP4 AVC: Abbreviation for MPEG-4 Advanced Video Coding. The MP4 AVC file format is used to store video files in a more manageable size wihout affecting the quality. It is also increasingly being used for storing video on iPods and similar portable devices. See also MPEG-4 Advanced Audio Encoding (above).

RM (RealPlayer): Used for playing streaming audio and streaming video. RM enables content to be delivered as a continuous flow of data with little wait time before playback begins. This means that you do not have to wait for your audio and video files to fully download before starting to view them: http://uk.real.com/realplayer/. RealPlayer enables you to download streaming files (e.g. YouTube videos) from the Web: see Section 2.2.2.6 (below).

WMV: Windows Media File. This is Microsoft's own file format. WMV is the same as ASF (see above) except that it can be downloaded instead of streamed from a server located at a distance.

DVD-Video discs use a special format that is different from all the above, namely MPEG-2. See Section 2.1.7 and Section 2.2.2 (above).

See aslo FLV.com, a glossary of abbreviations and terms relating mainly to audio and video formats, with links to a range of conversion tools.

See Bailey & Dugard (2007) on using digital video in the languages classroom.

Plug-ins for playing streaming audio and video

A plug-in is an extra piece of software that a Web browser needs to run certain elements of a Web page, e.g. animated sequences and audio or video clips. You will find that when you click on an icon that signifies the availability of streaming audio or video material, your browser will link with a plug-in. If the plug-in is not already installed on your computer then you will be able to download it free of charge. Web pages incorporating multimedia often need plug-ins such as Flash Player, QuickTime, Shockwave Player or RealPlayer.

If you have problems running animated sequences or video clips check that the relevant plug-in has been downloaded and installed on the computer that you are using.See also Section 2.2.1 above, headed Media players.

A podcast is a broadcast digital audio recording, made available via the Web in a way that allows the recording to be downloaded for listening at the user's convenience. The term vodcast is often used to describe a broadcast digital video recording, also made available via the Web. The term podcast takes its name from a combination of iPod (Apple's portable digital media player) and broadcasting, but podcasts and vodcasts do not necessarily require the use of an iPod or similar device. Podcasts and vodcasts can simply be downloaded to a computer and played using a standard media player program. See Section 3.5.2, Module 2.3, headed Podcasting, for further information.

Saving media files for use offline can be very straightforward, but it depends on the format in which they have been recorded. The procedure for saving audio and video files that have been recorded in WAV, MP3, WMV, MPG or AVI format is described in Module 2.3, Section 2.1.4 and Module 2.3, Section 2.1.5, but saving video clips from popular video sharing websites such as YouTube and Metacafe is a little bit trickier. The easiest way to save YouTube and Metacafe video clips (also some other formats) is to install RealPlayer on your computer (see Section 2.2.2.4 above). Once you have installed RealPlayer on your computer you will find that if you move your cursor to a point just above the top right of the video window when a video is playing, a tab will pop up with the message Download This Video. Click on the tab and RealPlayer will download the video to your computer's hard disc. See the Download YouTube Clips tutorial by Joe Dale at the CILT website.

There are many software tools available that enable you to capture streaming media and convert it from one form into another, e.g.

DVDVideoSoft offers a range of different converters.

FlashLynx: Download and convert videos from video sharing sites, including YouTube, MySpace and Google Video.

FLV.com offers a free FLV Converter, FLV Player, and FLV Downloader.

The Graphic Mania website lists 13 Useful Free Online Video Converters.

Replay

Converter: A tool for converting audio and video files, by Applian Technologies.

YouConvertIt: Free online media conversion. Requires email registration.

YouTube downloader: Download and convert YouTube videos.

Zamzar: Free online file conversion. Convert images, audio files, video files and document files from one format to another without having to download software. Send the URL to Zamzar and they email the converted file back to you.

Contents of Section 3

Multimedia clearly offers many exciting opportunities for language learning. The possibility of combining text, images, sound and video in a variety of activities was a major step forward in CALL, but many of the opportunities that this offers have simply not been seized. Most multimedia applications tend to be strong on presentation and weak in terms of pedagogy and interaction. It often appears that the new generation of software developers, i.e. from the late 1980s onwards, have overlooked or deliberately ignored everything that was learned by the previous generation.

CALL was highly regarded in its early days because of its ability to individualise learning. Language labs were welcomed for similar reasons. But language labs fell out of favour because of the "battery chicken syndrome" - i.e. rows and rows of students all doing more or less the same thing. The same began to happen with computer labs. The mindless drills that were offered in language labs were reincarnated in a different form in computer labs: see Davies (1997:28-29). Many multimedia applications have followed the same downward path; in spite of all the bells and whistles they are no more than a series of drills in glorious technicolor and stereophonic sound. Early CALL was undoubtedly primitive. The first microcomputers offered only white text on a black screen, and to a large extent early CALL was based on a behaviouristic, programmed-learning approach, which has now been largely discredited: see Section 3.2 above. Nevertheless, a good deal was learned in the early days about discrete error analysis, the importance of intrinsic feedback as opposed to extrinsic feedback, branching, the concept of a default route through a program, etc. And there were some good simulations, e.g Granville, and programs that made imaginative use of simple graphics, e.g. Quelle Tête and Kopfjäger - all of which were developed in the mid-1980s by Barry Jones. Many of the lessons that were learned are described in Laurillard (1993). Davies (1997:38) sums up this approach, citing Laurillard (1993):

The modern approach stresses the importance of guidance rather than control, offering the student a default route through the program as an alternative to browsing, and building in intrinsic rather than extrinsic feedback, so that the learner has a chance to identify his/her own mistakes.

See Section 8, Module 2.5, How to factor feedback into your authoring, on the distinction between intrinsic feedback and extrinsic feedback.

Warschauer (1996) defines three phases of CALL:

See also Section 3, Module 1.4, headed Warschauer (1996).

In his consideration of the pros and cons of multimedia, Warschauer uses the term hypermedia as a subset of multimedia in the sense that:

[...] multimedia resources are all linked together and [...] learners can navigate their own path simply by pointing and clicking a mouse. (Warschauer 1996)

Nowadays, it can be assumed that the majority of multimedia applications embrace the functions that Warschauer ascribes to hypermedia. Warschauer continues:

First of all, a more authentic learning environment is created, since listening is combined with seeing, just like in the real world. Secondly, skills are easily integrated, since the variety of media make it natural to combine reading, writing, speaking and listening in a single activity. Third, students have great control over their learning, since they can not only go at their own pace but even on their own individual path, going forward and backwards to different parts of the program, honing in on particular aspects and skipping other aspects altogether. Finally, a major advantage of hypermedia is that it facilitates a principle focus on the content, without sacrificing a secondary focus on language form or learning strategies. For example, while the main lesson is in the foreground, students can have access to a variety of background links which will allow them rapid access to grammatical explanations or exercises, vocabulary glosses, pronunciation information, or questions or prompts which encourage them to adopt an appropriate learning strategy. (Warschauer 1996)

According to Warschauer, one of the reasons why multimedia has failed to make a major impact is the lack of good quality programs, claiming that "computer programs are not yet intelligent enough to be truly interactive". This is true, although I would put it thus: the main reason why multimedia applications have not been adopted widely by language teachers is that software creators have been singularly lacking in imagination. Only a handful of multimedia simulations have been produced for language learners: e.g. A la rencontre de Philippe, Montevidisco, EXPODISC and Who is Oscar Lake? Language teachers certainly need more programs like these. Warschauer describes the Dustin simulation as follows:

The program is a simulation of a student arriving at a U.S. airport. The student must go through customs, find transportation to the city, and check in at a hotel. The language learner using the program assumes the role of the arriving student by interacting with simulated people who appear in video clips and responding to what they say by typing in responses. If the responses are correct, the student is sent off to do other things, such as meeting a roommate. If the responses are incorrect, the program takes remedial action by showing examples or breaking down the task into smaller parts. At any time the student can control the situation by asking what to do, asking what to say, asking to hear again what was just said, requesting for a translation, or controlling the level of difficulty of the lesson. (Warschauer 1996)

See also Section 5.10, Module 3.2, headed Branching dialogues.

Another feature of multimedia applications is that they tend to be short on feedback, offering the learner little help in identifying his/her mistakes. All too often a wrong response is accompanied by a "boing" and a correct response is accompanied by the sound of applause or fanfare - very irritating after the first few minutes. I worked my my through the first few lessons of a CD-ROM for beginners in Japanese which adopted this approach. I eventually got a good score, but a couple of days later I could not remember a single word of Japanese. There is a danger, however, of relying too much on the computer's ability to process the learner's input:

Where the student is generally working alone without the teacher, the computer has to reliably give the student the right kind of guidance and advice every time the program is used; there is no second wave of feedback that can come with a teacher's presence to act as backup. [...] The success, therefore of the computer in the tutorial role, hinges on how reliably the program manages the student's learning and on how timely, accurate and appropriate is the feedback, help and advice given. (Levy 1998:90)

Levy certainly has a point, and I have also been very critical of ICALL-based programs that rely heavily on input analysis (Davies 1997:35-39). The view I expressed at the time was that many designers of programs of this type were more interested in control rather than guidance, but see the following sections, which present a more positive point of view:

Levy has his doubts about simulations too:

As far as simulations are concerned, the potential threat of isolation and mere vicarious experience need to be considered. Virtual worlds, for example, might isolate or distance the individual from the real world. Such experiences, whilst having the potential to simulate real communicative situation, nevertheless remain illusory. (Levy 1998:90)

Here I think that Levy is off the track. Most people are well aware of the difference between simulations and reality; the surrealistic city in the Who is Oscar Lake? series, is clearly unreal - "surrealistic" might be a better word - and so are most of the characters. Simulations certainly have an important role to play in certain kinds of training, e.g. learning how to fly a Boeing 747, but it is not that easy to set up a simulation for developing communicative competence in a foreign language. It's difficult enough to set up live role-plays in the language classroom. As a language learner, I can only remember one role-play that I practised in the classroom actually going according to plan in reality. I was ordering food and drink in a restaurant in Hungary, and the waiter responded exactly as I anticipated. I wish I had had a tape-recorder with me at the time. Most of the time, however, I got totally unexpected and unintelligible responses. Now, with the advent of virtual worlds online, new opportunities are available to language teachers and learners: see Section 14.2.1, Module 1.5 on the virtual world of Second Life.

Multimedia is a new phenomenon. Technology is racing ahead of pedagogy and, unfortunately, often driving the pedagogy. Above all, there is a need for further research into how language students learn. We still know relatively little about the learning process, but what little we know is often disregarded by multimedia developers: see Chapelle (1997 & 1998) and Garrett (1998). As Chapelle puts it:

Why is there such a dissonance between even the most technically sophisticated work in CALL and SLA research? (Chapelle 1997:3)

This section addresses the key issues that need to be considered when evaluating multimedia sofware. See also:

A basic learning principle is that the learner makes progress by mentally processing the language he/she is learning and not by blindly pointing and clicking. Too many multimedia programs rely on what may be called the "point-and-click-let's-move-on-quick" approach. It is all too easy to be deceived by flashy presentations. I suppose it's symptomatic of the video age - let it all wash over the learner's head and if you're lucky something might eventually stick. When examining a new multimedia application it may be useful to ask yourself the following questions:

What other questions would you ask yourself? Think of a few! Have a look at Module 3.2, which is concerned with multimedia software design issues.

During the 1990s a large number of multimedia CD-ROMs were produced, aimed at a wide variety of language learners at all ages. Most of the CD-ROMs described below date back to this period and are no longer available, but they are good illustrations of the range of possibilities and constraints of multimedia, and the screenshots and descriptions that follow will be preserved at the ICT4LT site as a historical document. The current trend is to make everything available via the World Wide Web, but there are still certain advantages of using a CD-ROM compared to using the Web. For example, we are still waiting for the Web to deliver listen / respond / playback activities that compare favourably with those offered by the first AAC tape recorders in the 1960s.

For examples of Web-based resources and tools see Module 1.5, Introduction to the Internet, and Module 2.3, Exploiting World Wide Web resources offline and online. For a list of links to websites dedicated to learning and teaching a range of different languages - plus other useful tools - see Graham Davies's Favourite Websites.

Early CD-ROMs contained just text, e.g. the complete works of Shakespeare, the bible, a year's edition of a newspaper, a dictionary, or a 20-volume encyclopaedia. When PCs equipped with soundcards became more widely available, dictionaries and encyclopaedias were enhanced with sound, pictures and video, early examples being the Longman Interactive English Dictionary and Microsoft's Encarta. There are clearly advantages for the language learner in being able to play a sound recording of a dictionary entry, and a picture often helps clarify meaning. Nevetheless, dictionaries in book format have not gone out of fashion. I often find it quicker to reach up to my bookshelf and grab a dictionary rather than hunting around the Web. When I visited a translation agency a few years ago, I was surprised to see most of the translators consulting standard reference dictionaries in book format on their desks - especially as they were all using enhanced word-processing software that enabled them to work with a split-screen display showing source and target texts. When I asked one translator if she ever used an electronic dictionary, she said she occasionally used one to check a meaning but generally found such dictionaries unreliable and the entries too brief - and anyway she preferred to look away from the screen regularly to give her eyes a rest. She was, however, using a translation memory package: see Section 3, Module 3.5, headed Machine Translation.

All-in-One Language Fun and Kidspeak are typical examples of CD-ROMs that make use of just two media: cartoon pictures and sound. Both CD-ROMs are designed for young learners.

There is no text on screen in All-in-One Language Fun, because some members of its target audience (ages 3-12) will not have learned to read, and no input is required at the keyboard. All-in-One Language Fun concentrates entirely on listening skills using multimedia versions of familiar games: e.g. Jigsaw Puzzles, Memory Teasers, Simon Says, Bingo, Telling the Time, Dress the Child, etc. Five languages are included on one CD-ROM: French, German, Spanish, Japanese and English. Unlike many programs of this type that I have criticised for falling into the "point-and-click-let's-move-on-quick" category, this one does a good job. It is difficult to carry out many of the tasks without understanding the language that is presented. Although this CD-ROM is aimed at young learners, many adults might benefit from using it too. An adult learner told me that for the first time in her life she managed to sort out the difference between dative and accusative after prepositions of location or movement towards a location in German - there's a useful little activity that involves sending a mouse to different locations in a variety of rooms in a house.

Screenshot: All-in-One Language Fun, Selection of Games

Kidspeak is aimed at slightly older learners (6-plus) and there is a limited amount of text on screen but, like All-in-One Language Fun, the program makes use mainly of cartoon pictures and sound. The emphasis in Kidspeak is, again, on understanding language. Kidspeak presents language through a variety of games. Each topic offers four entertaining games and a song. Each game offers three levels of difficulty to keep the child challenged. There are also printable activities. Language skills include the alphabet and word recognition, correct pronunciation, understanding simple sentences, using plural and singular, telling the time, greetings, colours, clothing, weather, travel, food - over 700 words per language. Portuguese, French, Spanish, German, Hebrew, Chinese, Japanese, Indonesian, Italian and Korean are all included on the two CD-ROMs.

Screenshot: Kidspeak, Spanish

A technique that is often used in packages for young children is the clickable image. One of the first programs of this type was Just Grandma and Me in Brøderbund's Living Books series, first published in 1993. As well as making use of clickable text in a choice of three languages (English, Spanish and Japanese), the learner can click on images on screen, which activate amusing animated cartoons accompanied by spoken words and sound effects.

Screenshot: Just Grandma and Me, English

The Tortoise and the Hare is one of the most popular Living Books packages. Aesop's fable of the race between the tortoise and the hare is presented here in a new light. Simon, the storytelling bird, acts as the narrator. The full text of the story appears on screen (in English or Spanish) and is first read out loud by a native speaker. The learner can click on any word in the text in order to hear it pronounced, but clicking on items in the pictures that illustrate the story brings a rich variety of surprises: chimney pots that wish one another "Good morning" or "Buenos dias", the politically correct tortoise that insists on newspapers being recycled, the rapping beaver - and many others.

Screenshot: The Tortoise and the Hare, Spanish

The New Kid on the Block is another Living Book, but with a different approach. Instead of dealing with just one story, this CD-ROM contains a series of amusing poems in English for young children, all of which have been written by Jack Prelutsky. The aim is to bring the poems to life. The learner can listen to the whole text of each poem and can then click on any word. A native speaker (English) reads the individual word out loud and the meaning of the word is acted out in a series of animated cartoons. The animations are both memorable and humorous, proving that poetry can be fun.

Screenshot: The New Kid on the Block

There is a wide choice of CD-ROMs for children beginning a language at secondary school level. The following two CD-ROMs are typical examples. Unfortunately, the choice narrows as the learner reaches higher levels. See The Ashcombe School's Modern Foreign Languages website.

En Route: This CD-ROM is divided into ten comprehensive sections covering a wide range of everyday topics. Each section deals with a different topic and contains a variety of exercises. The package enables the user to record his/her own voice and compare it with a French native speaker. Students may also measure their progress via continuous assessment. There are hundreds of photographs, illustrations, video and audio clips, and online grammar help. The schools edition also contains a scrapbook which, used in conjunction with the CD-ROM, allows the learner to view, select and save video footage, images, audio material and text into their own files. This CD-ROM corresponds to Key Stage 3 of the National Curriculum.

Screenshot: En Route

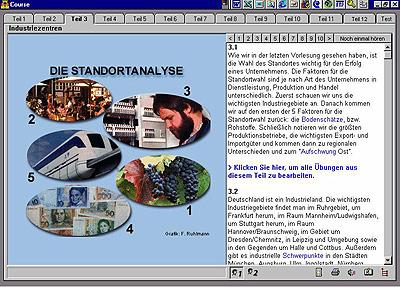

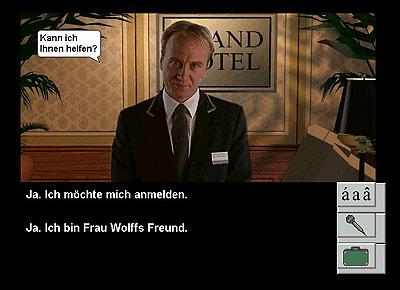

Unterwegs: This CD-ROM is divided into ten comprehensive sections covering a wide range of everyday topics. Each section deals with a different topic and contains exercises designed to teach German in a natural, structured and progressive way. The fully interactive program enables the student to record, listen and compare his/her own speech and pronunciation with the German spoken on the disc. Students may also measure their progress via continuous assessment. This colourful package, with hundreds of photographs, illustrations, video footage and audio clips, even includes online grammatical help. The schools edition also contains a scrapbook which, used in conjunction with the CD-ROM, allows students to view, select and save video footage, images, audio material and text into their own files. This CD-ROM corresponds to Key Stage 3 of the National Curriculum.

Screenshot: Unterwegs

There is a dearth of good CD-ROMs for the advanced learner, but I have identified three examples, described below, which offer three very different approaches.

LINC is a package for advanced learners aged around 16+. Versions in French, German, Spanish, English and Dutch are already available, and other language versions are planned. Contents: 10 video topics with transcript and explanation of cultural issues; hundreds of exercises on reading, writing, listening, speaking, vocabulary, and grammar with feedback and pedagogical help screens. Tools: Integrated on-screen video, audio and text; reference grammar; mini-dictionary; WWW-access for further exploration; email facility for contact with other learners.

Screenshot: LINC, German

La neve nel bicchiere is a CD-ROM designed for use by learners of Italian at higher-intermediate/advanced level. It was created between 1992 and 1997 by the Hypermedia Italian Team (HIT) at Coventry University with the help of students of Italian and has as its text base Nerino Rossiís novel La neve nel bicchiere. The material contained on the CD-ROM is also suitable for teaching Italian to mother-tongue students. The novel La neve nel bicchiere and the CD-ROM describe the historical and social conditions of an Italian family over a period of seventy years (1880-1950). The material on the CD-ROM is particularly suitable for the teaching of a variety of national and regional topics, such as: Anarchism and Socialism, State and Church, Women in Italy, Fascism, From Peasants to Bourgeoise, Italy at War (Lybian War, First World War, Second World War). Information on integrating the CD-ROM into the Italian curriculum is also included in a printable text file.

Screenshot: La neve nel bicchiere

European Business Environment, Germany: A self-study lecture course in German with activities and tasks. The CD-ROM consists of three parts:

Screenshot: European Business Environment, Germany

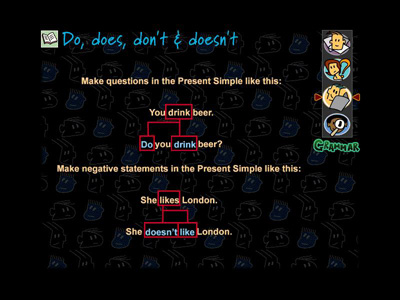

Grammar went out of fashion some years ago, but now it is making a comeback. Multimedia offers ways of making grammar more interesting and entertaining. The following two CD-ROMS are good examples.

The Grammar ROM: Grammar for learners of English as a Foreign Language. This is one of the few CD-ROMs I have seen that concentrate on English grammar. All the key points of English grammar are covered: Verbs, Nouns and Articles, Modals, Conditionals The Passive, Adjectives and Adverbs, Questions, Prepositions, Clauses, Links, Reported Speech, Phrasal Verbs, Gerund and Infinitive. The learner can choose between English, French, German, Spanish and Italian as the language of on-screen instructions and spoken instructions. There is an online glossary and grammar reference section, accompanied by 300 exercises: e.g. multiple-choice and gap-filling exercises, comprehension exercises relating to writte text and audio and video recordings, re-ordering of sentences, sequencing of activities. The CD-ROM includes lively cartoon drawings, authentic sound recordings, and motion video sequences taken from videos written by Ingrid Freebairn and Brian Abbs: A Family Affair, Two Days in Summer, Face the Music.

Screenshot: The Grammar ROM

French Grammar Studio: This CD-ROM has been designed to help students prepare for the French GCSE examination and as a stand-alone program for practising grammar skills. The disc is divided into two sections: (i) Photostories and (ii) The Grammar Factory. Photostories provides students with the challenge of building an audiovisual presentation based on locations within France. To complete a photostory correctly, the student must construct a commentary by selecting from a number of grammatical options. Pop-up help is available if errors are made, together with a more detailed explanation of all points of grammar. The completed photostory can then be replayed as an audiovisual presentation. There are 18 photostories to choose from and these have been illustrated with specially commissioned photographs from various French locations, and the audio is provided using native French speakers. The Grammar Factory provides a comprehensive explanation of French grammar. Each point is illustrated with extensive use of animation. Practical exercises enable the user to consolidate learning. This CD-ROM is supported with on-screen help, support materials which can be printed, and a large contextual French-English dictionary of the words on the disc

Screenshot: French Grammar Studio

Now! This series of CD-ROMs is a good example of the use of multimedia to promote reading skills. The package includes sets of authentic stories and articles that learners can read at their own speed. A split screen is used with the story on the top half and individual words and phrases translated on the bottom half. Help screens provide grammatical notes. The stories and articles also aim to give the student an understanding of a country's culture. In addition, there are pronunciation and listening comprehension exercises, which are reinforced through the use of sound and authentic pictures and video (see screenshot below). The Now! series incorporates Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), enabling the learner to record his/her own voice and get a visual impression of what it looks like, using a voiceprint: cf. the examples of screenshots of voiceprints taken from the Talk to Me and Tell Me More CD-ROMs in Section 3.4.7 below. Available in Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, French, German, Irish, Italian, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Swedish.

Screenshot: German Now!

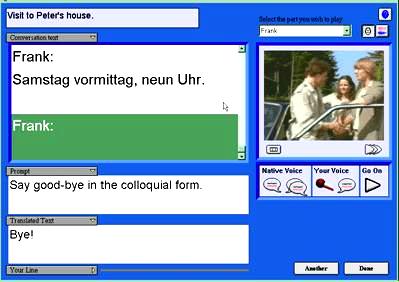

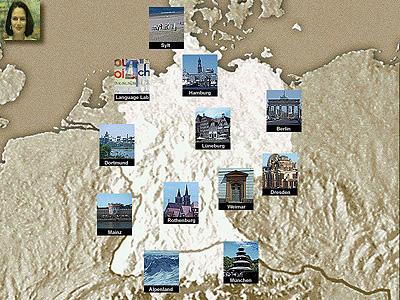

RealTime is an interactive CD-ROM course for near-beginners. This CD-ROM series provides the student with background information on the country via dialogues and photostories, which are based in places of historical or cultural interest - a clickable map of the country serves as a menu (see screenshot below). RealTime also reinforces grammar and vocabulary by means of over 400 interactive exercises. The student is automatically provided with practice in his/her weaker areas and can record his/her own voice and compare it to that of a native speaker. Available in French, German and Spanish (Castilian).

Screenshot: RealTime, German

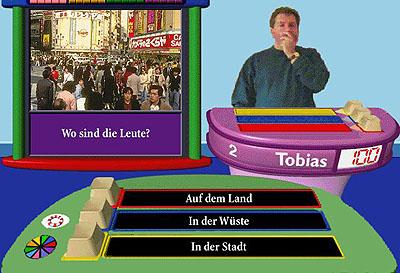

World Talk: This CD-ROM targets the intermediate level language learner, following on from EuroTalk's beginner-level Talk Now! range. Topics covered include: the calendar, sentence building, asking directions, the weather and numbers. There is a section that takes the format of a TV quiz show, in which the learner can play against a resident champion - depicted in entertaining video sequences (see screenshot below) - or in a one-to-one match with a friend. Available in a wide range of languages, e.g. Afrikaans, American English, Arabic, British English, Cantonese, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, Japanese, Mandarin, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese (Continental), Russian, Spanish (Castilian) Swedish, Thai, Turkish, Welsh, Xhosa and Zulu. EuroTalk also publishes a range of DVD-ROMs.

Screenshot: WorldTalk, German

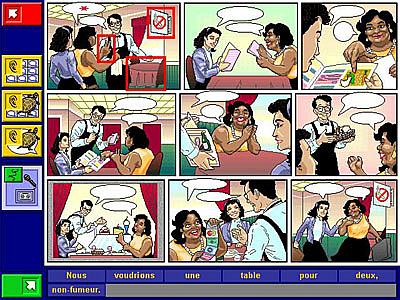

Smart Start: This is the new name for the TriplePlay Plus series of CD-ROMs, which for a short time was advertised in certain countries under the name Multimedia Language System. Confused? Well, this happens all the time in the CD-ROM business: names continually change, and firms pop up overnight and then disappear. The general form of this package is the same as the popular original TriplePlay Plus, which includes Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and listening exercises linked to text on screen, e.g. the rearrangement of jumbled sentences forming part of a dialogue. With ASR, when you record your own voice the computer analyses your response and compares it to the model answer: see also the CD-ROMs described in Section 3.4.7 below. A "ping" indicates that you are close, and a "boing" indicates that what you said cannot be recognised. ASR is not 100% reliable, however, and may result in a learner's intelligible attempt to pronounce a word or phrase being rejected. Nevertheless, ASR has been observed to be highly motivating, encouraging the learner to make several consecutive attempts to get his/her pronunication right. Alternatively, you can just play back your own recording and compare your attempts at pronouncing words and phrases with the native speaker model. The learner can choose from three levels of language learning, each one building upon the last. There are six topic categories: Food, Numbers, People, Activities, Places & Transportation, Home & Office. Within each activity the learner can play a language-learning game, choosing from many different games with multiple degrees of difficulty, practice screens, and clues. Colourful comic-strips are used to practise conversations (see screenshot below). The learner can choose different roles in the conversation, listen to the dialogue in its entirety, or in chunks at different speeds, with or without text on screen.

Screenshot: Smart Start, French

The following two CD-ROMs make extensive use of Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) software. The Smart Start and the Now! CD-ROMs also use ASR software: see Section 3.4.6 above. ASR is not 100% reliable, however, and may result in a learner's intelligible attempt to pronounce a word or phrase being rejected. Nevertheless ASR has been observed to be highly motivating, encouraging the learner to make several consecutive attempts to get his/her pronunciation right. For further information on ASR see Section 4, Module 3.5, headed Speech technologies.

Talk to Me: Talk to Me allows language learners to have an interactive conversation with the computer. The focus is on improving grammar skills and listening comprehension, while enhancing vocabulary and written expression. In addition, the quality of the student's pronunciation is indicated via voiceprints and a scoring system that make use of Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) software. Talk to Me includes a variety of exercises, for example:

Dialogue Exercises: The computer talks to you; you answer the computer through a microphone, the computer recognises what you say and responds to your answer.

Picture/Word Association

Crossword Puzzles:

Video- based exercises:

Simulated Conversations: Enjoy a conversation with the computer, where the sequence of questions and answers simulates that of real-life conversation. See Screenshot 1 (below).

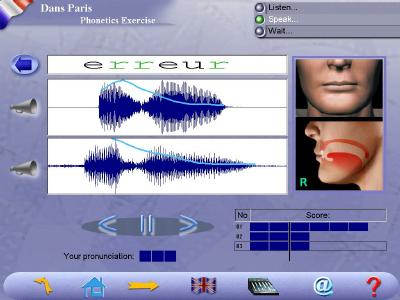

Sentence Pronunciation and Phonetics Exercises: A model sample sentence or word is shown and you listen to it and then repeat as often as you wish, imitating the computer's model. Access to a large number of sentences and individual words for phonetics practice allows you to practise pronunciation for hours.

Screenshot 1: Talk to Me

Screenshot 2: Voiceprint from Talk to Me

Tell Me More & Tell Me More Pro: Tell Me More takes Talk to Me's approach a step further, and Tell Me More Pro allows the teacher to adapt the software to the level and needs of the student. The teacher can determine the activities to which the student has access, and the order in which they should be performed. Parts of the program itself can be modified to suit the student's learning needs: for example, the acceptance level of pronunciation, display of texts and translations. The teacher can also consult progress reports for every student for each session spent, either in the form of statistics or in greater detail. The teacher can also check the student's spoken work. The contents of each lesson may be printed out. Grammar lessons are accessible to the student at all times. Each rule is illustrated by cartoons and clear explanations. Videos deal with different subjects (e.g. London, Paris, renting a villa, animals, sports, etc.) and are followed by multiple-choice comprehension exercises. A glossary is provided, giving the student access to the translation of each text and each word encountered during the lesson. The CD-ROM includes a variety of exercises in which Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) plays a key role. A voiceprint (see screenshot below) is used to help the learner match his/her voice against the native speaker's voice. Available in French, German, Spanish (Castilian), Italian and English.

The Ashcombe School's CD-ROM Reviews page describes Tell Me More Pro as follows:

Gets the pupils really concentrating on the quality of their pronunciation. Great to have pupils 'talking' out loud, all at once, with good accents! The speech recognition software gives pupils 'scores' for pronunciation, and they make a real effort to improve them.

Screenshot: Voiceprint from Tell Me More

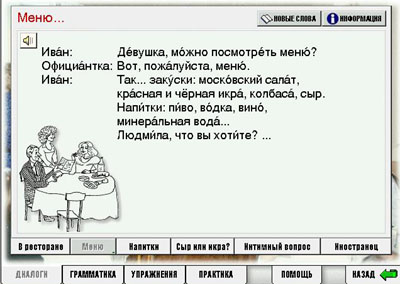

Ruslan: A model multimedia application that should be emulated by others. This is a complete multimedia CD-ROM course for beginners which includes dialogues, grammar explanations, background information, vocabularies, around 300 interactive exercises, dictionary, hints for travellers, video excerpts and more. The on-screen instructions are in Russian, with a click for translation if you need it. Help includes a full index search for topics. Unlike many multimedia applications, this one actually aims to teach, adopting a step-by-step approach to the presentation of the Russian language, from the alphabet onwards. This CD-ROM is based on the Ruslan course by John Langran and Natalya Veshnyeva, and the programming is by Mike Beilby.

Screenshot: Ruslan 1

The Who is Oscar Lake? CD-ROMs are good examples of simulations for language learners. Like many simulations, which date back to very early text-only computer games known as adventures, the learner has to "discover" a path through the simulation in order to achieve a particular aim or arrive at a destination. In modern simulations the learner practises language on the way. In the Who is Oscar Lake? series the learner plays the key role in a mystery story. The story begins with the learner being given instructions by telephone to travel to a capital city. As the learner tries to solve the mystery he/she is confronted in the target language with videos of an interesting cast of characters. The video scenes run under QuickTime and are a vital component for the interactive sequences: e.g. in an early sequence the learner books a train ticket, hands the ticket clerk the money, picks up the ticket and puts it in his/her "briefcase".