ICT4LT

Module 3.1

ICT4LT

Module 3.1 ICT4LT

Module 3.1

ICT4LT

Module 3.1This module presents five different approaches to setting up and managing a multimedia language centre. Five case studies are presented, preceded by a Foreword by Graham Davies, who set up and managed the National Centre for Computer Assisted Language Learning (NCCALL) at Ealing College London, 1985-1990, and the Multimedia Language Centre at Thames Valley University, 1990-1993.

This module should be read in conjunction with:

It is also recommended that the reader also looks at the following publication:

Davies G., Bangs P., Frisby R. & Walton E. (2005 - regularly updated) Setting up effective digital language laboratories and multimedia ICT suites for Modern Foreign Languages, London: CILT.

New case studies are being sought

for this module: The case studies presented in this module date back a few

years. Although the principles of managing a multimedia language centre remain

much the same, there have been dramatic changes in the hardware and software

that is now available. If you would like to contribute your own case study please

contact Graham Davies via our online Feedback

Form.

This Web page is designed to be read from the printed page. Use File / Print in your browser to produce a printed copy. After you have digested the contents of the printed copy, come back to the onscreen version to follow up the hyperlinks.

Graham Davies, Editor-in-Chief, ICT4LT Website.

Richard Hamilton, Cox Green Comprehensive School, Maidenhead, UK (Case Study 1).

Berthold Weidmann, St George's Academy, Sleaford, UK (Case Study 2).

Stephan Gabel & Lienhard Legenhausen, University of Münster, Germany (Case Study 3).

Mr Valère Meus, University of Ghent, Belgium (Case Study 4).

Helen Myers, The Ashcombe School, Dorking, UK (Case Study 5).

i. Why use technology?

ii. Skills and staffing

iii. Hardware and software

iv. What does it cost?

v. Keeping an inventory

vi. Copyright issues

vii. Self-study

viii. A variety of approaches

ix. Discussion topics

x. Further reading and resources

The modern language centre manager has to cope with a bewildering range of equipment, and increasingly demanding language teachers and students. Unfortunately, administrators in schools and universities are prone to regard the use of technology as a means of cutting down on staff, in the belief that "throwing hardware at a problem will save money". The result is that many language centres are underutilised - just like their predecessors, the language lab, interactive video, satellite TV, etc. See Davies (1997), who refers to a number of mistakes that were made in the past regarding the use of technology in teaching and learning foreign languages and the lessons we can learn from them. Using technology to teach foreign languages definitely does not save money (ibid. (1997:30). See also Felix (2003), regarding some of the myths surrounding online learning. See Section Module 2.3, headed Web-based CALL, for further information on online learning. See also Mark Pegrum's wiki on Myths of E-learning: http://e-language.wikispaces.com/myths

Technology is much more expensive than "chalk and talk", requiring large amounts of funding for the acquisition of equipment and computer software, acquisition of audio and video materials, acquisition of printed materials, provision of technical support staff and resources assistants, and - two frequently overlooked areas - training of teaching staff and materials development: see Section iv, What does it cost? And there is no economy of scale: the bigger and the more sophisticated a multimedia language centre becomes the more it costs; the more students you have to deal with the more complex the technology becomes, and consequently the more maintenance the technology requires because students expect that it will work 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year.

So why use technology? Have another at Section 3, Module 1.1, headed Why should the language teacher be concerned with new technologies? A number of important reasons for using new technologies are set out in this section. Can you think of any more?

Section 3, Module 1.1 attempts to answer the question How effective are new technologies in promoting language learning? Hard evidence is difficult to obtain, but there is an increasing amount of anecdotal evidence and research evidence indicating that, under the right conditions, new technologies can make a significant positive impact - which is also pointed out by the contributors to the case studies in this module.

Managing a multimedia language centre is a demanding and challenging activity. It requires a wide range of skills and knowledge: e.g. technical know-how, budget management skills, an ability to communicate and to deal with people, knowledge of copyright issues, and - of course - a knowledge of foreign languages and language teaching methodology. When I first embarked upon my career as a language teacher, technology was very much a low-key activity. The only "technical" devices that I used were a slide projector, a tape recorder, and a record player. In the mid-1960s I was introduced to the language laboratory, and in the 1970s I began to use computers, setting up my first computer lab for language students in the early 1980s. In the early 1990s I set up a full-blown multimedia language centre at Thames Valley University (TVU), comprising six language laboratories, 40 networked and stand-alone computers, four satellite TV dishes and a viewing room, a recording studio, and a range of video and audio playback and recording facilities. Over the years I had accumulated a good deal of knowledge about language learning and teaching technology, but I was not a one-man band; I was assisted by five members of staff: an audio/video technician, two resources assistants, a computer network manager, and a secretary. And I always regarded staff training as an ongoing and unending process - for which I set aside a reasonable amount of funding each year. The centre worked well, with every seat taken at peak times, and then the budget cuts came, but that's another story...

Hardware choices are more often than not determined

by local circumstances, e.g. whatever deals your institution has struck with

hardware suppliers and the personal preferences of the ICT co-ordinator. Many

language teachers complain bitterly that they have no say in the matter. It

is clear from the case studies in this module that local circumstances and personal

preferences play a key role.

No less important is the question of the budget your institution allows for

looking after the hardware. As Richard Hamilton points out in Case

Study 1, a computer network can be a burden rather than a blessing if no

money has been allocated to run it. Managing a computer network takes time and

requires high-level technical skills. There is no point in setting up a network

if a properly trained member of staff is not available to run it; you're better

off setting up a battery of stand-alone computers instead.

There has been a good deal of discussion concerning the networking of multimedia CD-ROMs. My own experience as a partner in an educational software business that has sold hundreds of multimedia CD-ROMs to schools and universities is that teachers attempting to run CD-ROMs on computer networks have caused us the biggest imaginable headache we have ever experienced in terms of after-sales technical support. The technical situation has improved considerably in recent years, but it is still far from perfect. Networks run more quickly but CD-ROMs have become more complex. It is virtually impossible to give a straight "yes" or "no" answer to the question "Can I run this CD-ROM on a network?" The only sensible answer is "Possibly - it depends on your network manager".

Networks are great for delivering certain kinds of software to a large number of workstations, e.g. word-processing packages and dictionaries or encyclopaedias on CD-ROMs. But networks can be a nightmare if you intend to use them to deliver interactive multimedia CD-ROMs containing lots of sound files and video files. One-way traffic is fine, but two-way traffic involving students recording their own voices and interacting frequently with centrally-located CD-ROMs can be bad news. Most interactive multimedia CD-ROMs are designed to run on computers equipped with their own CD-ROM drives and hard discs. One way round the problem is to transfer the contents of each CD-ROM to the network hard drive - a solution that has been adopted by The Ashcombe School: see Case Study 5. Hard drives can be accessed much more quickly than CD-ROMs, but transferring the contents of a CD-ROM to a hard drive also has important copyright and licensing implications: see Section (vi) below. See also the Appendix, Module 2.2, Networking CD-ROMs and DVDs.

Using a contractor for network management

In theory, it sounds like a good idea for small educational institutions that lack in-house expertise to use an outside contractor for network management. In practice, however, this can be fraught with problems. One school has reported that it took a full six months to get their contractor to set up an authoring package in a way that was convenient both for teachers and for students. The main reason for the delay was that the contractor in question wanted to exercise a high degree of control over which programs could or could not be installed on the network, and it took months of negotiation and persuasion before the teachers got what they wanted. A number of schools have reported that lack of knowledge about CALL software on the part of the contractor led to programs being installed in an unsuitable way, e.g. one contractor only installed half of a software package, not realising that it consisted of two parts, one to be used by the teachers to generate exercises and one to be used by the students to do the exercises. As for multimedia applications, this is another grey area as far as contractors are concerned. Very few, it seems have the faintest idea of the important role that images, sound and video play in language learning and teaching - with the result that multimedia applications are often set up incorrectly. I suppose this is not surprising - how many ICT specialists in the UK have a track record of success in language learning?

An important piece of hardware that must be available in every computer room is a telephone, preferably a cordless telephone. Most technical problems that arise in the course of setting up and maintaining computer hardware and software can be sorted out by telephoning the technical support service of the supplier. The support service staff of the supplier will, however, expect you to be setting at your computer when you phone them so that you can tell them what appears on the screen when you carry out certain actions. Needless to say, you must also able to give the support staff details of serial numbers of your hardware, version numbers of your software, etc.

Hardware doesn't work without software but, regrettably, administrators rarely allow enough funding for the purchase of new software along with the purchase of new hardware. For some reason or other, it is assumed that the hardware will work on its own or that software will be available free of charge or at an unrealistically low cost. Furthermore, it is assumed that it is unnecessary to upgrade software when new hardware purchases are made. This is rather like assuming that all your old vinyl 33rpm records will continue to run on your new CD player. New hardware = new software. A realistic budget has to be allowed for:

Wireless networks and wireless classrooms are good news: no more trailing cables to fall over. Wifi (wireless fidelity), also known as wireless networking, is a way of transmitting information without cables that is reasonably fast and is often used for notebook computers within local area networks, e.g. a university or school campus. Wifi systems use high frequency radio signals to transmit and receive data over distances of several hundred feet. Wifi networks can also be found in many public places these days, e.g. airports and hotels. On the other hand, there is some concern that long exposure to wifi signals can damage one's health. At present, the evidence does not appear to be conclusive.

One question that I am often asked is: "What kind of budget should I allow for setting up a multimedia language centre?" Well, there's no magic answer. You might as well ask: "How long is a piece of string?" The most important point to bear in mind is how the budget is divided up not how big it is. The ideal budget should be divided as follows:

You probably have a number of hardware items at home, e.g. a videocassette recorder, a hifi system and a DVD player. Think carefully for a minute: How much have you spent on the software that runs on this hardware? You will probably find that your collection of VCR tapes (blank and pre-recorded), CDs and DVDs is at least equal in value to the hardware and possibly worth a lot more. The same is true of computer software - or it should be. The value of the software installed on my personal computer is three times that of the computer system itself. Be prepared to spend a lot of money on software after making hardware purchases.

Unfortunately, administrators and headteachers have a different perspective, usually allowing 90% of the budget for hardware, 10% for software, 0% for staff training and materials development, and 0% for contingency - which is an almost absolute guarantee of failure. The problem has been exacerbated in recent years as a consequence of the advent of the World Wide Web and the expectation that everything the language teacher needs - or any other teacher for that matter - will be for free. The trend is changing, as Felix points out:

A noticeable and interesting development is the spread of commercialisation even in sites that started off as free but have changed, if only by including banner advertising and a shop. The trend is not yet powerful enough to justify predictions that the Web will eventually split into quality sites for which users have to pay and free sites that are of poor quality, but there are signs of change. Given the expense involved in creating, running and updating any site, the chances must be that the best material will be developed by sites that can rely on costs being covered by income generated, even if [...] this is not a trouble-free option. (Felix 2001:189-190)

A number of small software developers specialising in software for modern languages have gone bankrupt in the last two years, and it is only now that language teachers are beginning to realise that this has left a big gap. Language teachers need an array of different software packages to make a success of a multimedia language centre, and the World Wide Web cannot satisfy all their needs: see, for example, Module 2.2, Introduction to multimedia CALL. Throwing hardware at a problem has never worked: see Section (i) Why use technology?

Having bought the software, you need to set aside a realistic budget for training staff how to use it. As a veteran computer user with over 25 years of experience, I am always reluctant to upgrade the software that I use on my own business computer systems as I know that it will cost me dearly with regard to the time that I will have to spend learning how to use it and that it will certainly result in a temporary loss of efficiency until I have mastered the new features that will save me time in the longer term - and then I have to pass on my newly acquired skills to my colleagues. Training is an investment for the future.

Keeping an inventory of equipment and learning materials is one of those drudge jobs that learning centre managers hate but have to do. The importance of this task should not be underestimated. As a language centre director, I ensured that details of each hardware acquisition were entered into a database, with a note of the model and serial number, supplier, date of acquisition, etc. The same was done for computer software acquisitions, and a file of suppliers' delivery notes and invoices was maintained. This sounds tedious, but it made life much easier if anything needed to be repaired, maintained or replaced, or if insurance claims had to be made in the case of equipment that was damaged or stolen. Records were kept of obsolete items of equipment that had been scrapped or sold, so there was never an argument as to their whereabouts.

We deal with copyright issues in detail in our General guidelines on copyright, which is a general introduction to copyright, drawing on a variety of sources.We also refer copyright in:

Record keeping: computer software

Keeping records of computer software acquisitions is just as important, possibly more important, than keeping records of hardware acquisitions - especially in view of the copyright situation regarding software. Software can easily be copied, and it is essential that a language centre possesses only legitimate copies of all the software it uses. Educational institutions are public places and can be caught out in surprising ways. My own business was contacted some years ago by a local school that had received a letter from the Federation Against Software Theft (FAST) asking the school to explain why a pupil at the school had brought home a floppy disc containing a copy of our software. I presume a conscientious parent, possibly a computer consultant or police officer, had reported the school to FAST. The floppy disc was in fact a legitimate copy - one of many student discs that we had supplied to the school - but we had to contact both FAST and the school to verify that everything was above board.

The plus side to keeping proper records of software acquisitions is that software upgrades can be obtained at discounted prices, perhaps only 25%-30% of the full price - providing one can provide evidence that one already has legitimate copies of the previous versions. Schools and universities can save themselves a fortune if they keep proper records.

Printed materials

Regarding printed materials, there is the (true) story of a supply teacher who arrived at a school where to take over the classes of a teacher on sick leave. He called in at the school office to collect the work for the classes he was due to take and was given a pile of 30 photocopies of a chapter from a book that he had written! He left immediately with the evidence and the school was taken to court, found guilty of a breach of copyright and had to pay a fine of several thousand pounds. One cannot be too careful. The following warning message appears in the catalogue of a UK publisher. This sums up UK copyright law very succinctly:

The law allows for a reader to make a single copy of a part of a book for purposes of private study. It does not allow the copying of entire books or the making of multiple copies of extracts. Under no circumstances may schools photocopy materials for use in self-access centres, unless they have registered with the CLA (Copyright Licensing Agency) or an associated licensing agency and allow/use photocopying strictly in accordance with their regulations. If a school wishes to have multiple copies of a part of a book in a self-access centre, then it must purchase the necessary number of printed books. There is no formal objection to schools physically cutting printed texts into parts and reassembling them in a way that seems appropriate, providing the books or parts of books are not then resold. It is not, however, a practice we would recommend. In the case of audio recordings, it is permissible for a school to make a copy of an audiocassette, keeping the original as a backup. Only one copy may exist at any one time. A school may copy different parts of an original audiocassette onto several cassettes, providing that no part of the original exists in more than one copy at any one time. Therefore, if a school wishes to have three copies of one part of an audiocassette, it must have three originals. No copying, single or multiple, of videocassettes is permitted. [Editor's Note: This last sentence is also given particular prominence in the original text.]

The publisher that wrote the above is known to be particularly generous regarding copyright in an educational environment; other publishers are much tougher, and should be contacted for clarification if necessary. The final sentence concerning video is significant. Video and still images are areas in which the language centre manager needs to tread very carefully. Putting together compilations of video clips, for example, on tape or in digital format is simply not allowed by most publishers and broadcasters. Copying or modifying a still image is also strictly prohibited - and not necessary as there are masses of copyright-free images available on CD-ROMs or on the Web.

Copyright and video: a cautionary tale

Another (true) story illustrates the dangers of paying insufficient attention to copyright ownership of video material. Two of my colleagues had collected video clips from TV news broadcasts that they wished to use in conjunction with a book they were writing. Having produced most of the written text, they then sought permission to use the video clips. This task proved impossible, however, as the TV companies referred them to the various news agencies that had supplied the clips, but on contacting the news agencies they were then referred to individual freelance cameramen and journalists who had supplied the clips to the agencies, and so it went on... They discovered that a news clip is often supplied for broadcast on just one day or two or three days in succession. The project had to start all over again, but they got it right the second time. The trick is first to locate copyright-free video material or video material for which copyright clearance can easily be granted, and then to create materials exploiting it. This is a point that was emphasised by Jean-Claude Bertin in his presentation at CALICO 1999, where he demonstrated his Learning Labs package that enables the exploitation of video clips. He had found, for example, that copyright clearance is often readily granted on advertising or publicity videos.

Self-study, self-access, learner autonomy - call it what you like - is a growth area but often misunderstood. Self-study is an important aspect of a multimedia learning environment and features prominently in the case studies in this module, but self-study doesn't happen by magic. An enormous investment of time is essential for materials development and creating the right kind of atmosphere for efficient self-study. I recall one member of the language teaching staff at Thames Valley University who was released from teaching duties for a whole year in order to create sets of self-study materials for EFL students: e.g. worksheets, log sheets, ideas for things to do, reorganising the layout of the self-access room, publicising the facilities, etc.

New roles have to be defined - with appropriate training - for resources assistants, who have to take on an advisory role as well as issuing materials for students' use and helping students' use the technical equipment. Providing a centre is properly equipped and staffed, and providing one pays due regard to copyright, self-study and distance learning are probably the most fruitful ways of exploiting the facilities of a modern multimedia language centre.

A new job description has emerged in recent years, i.e. that of the language advisor (Mozzon-McPherson & Vismans 2001).

See also Section 6, Module 1.4, headed Self-access learning.

The following case studies illustrate a variety of approaches to managing a multimedia language centre. It is clear from these case studies that planning and managing a multimedia language centre requires a high level of expertise, which in the end will - or should - determine the choice of equipment and how the centre is managed, e.g. to network or not to network, and to what extent self-access is feasible.

The case studies have been chosen because they demonstrate quite different approaches:

Case Study 1: The language centre at Cox Green Comprehensive School shows what can be done with limited technical support. Richard Hamilton is virtually a "one-man-band" - a language teacher turned ICT expert, who has been successful in attracting funding from a local business. The students at Cox Green School use the centre both as part of their regular weekly class-contact hours - integration is the watchword (see Module 2.1) - and as a self-access centre. Richard has opted for a battery of stand-alone computers as he lacks the time and expertise to manage a network.

Case Study 2: The Brealey Centre at St George's Academy is an example of the "high-tech" approach. The school is committed to promoting technology as a subject discipline throughout the school. Berthold Weidmann therefore benefits from considerable technical expertise in-house and within the local education authority. In contrast to Cox Green's centre, networking within St George's and to the outside world is a significant feature of The Brealey Centre. The school has also benefited from the injection of additional funding from a private benefactor, which enabled the purpose-built language centre to be set up.

Case Study 3: The solution described by Stephan Gabel and Lienhard Legenhausen was to set up a student support team. Student autonomy in this case study means much more than students studying independently; they also play a key role in the management of the centre. The self-access centre at the University of Münster relies heavily on student support, fostering the concept and practice of learner autonomy. A problem that this centre shares with Cox Green School (Case Study 1) is the lack of funding for permanent support staff.

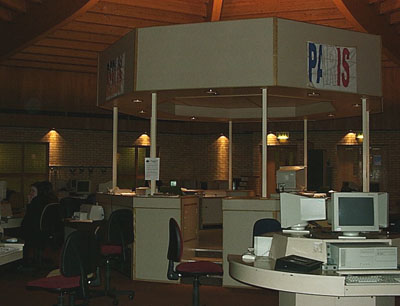

Case Study 4: The Language Centre at the University of Ghent is a good example of a centre which is in the process of "going digital" - including audio recordings that were previously available in a traditional language lab. Valère Meus and his colleague Jan De Baere (who has now moved to another institution) were kind enough to show me round this centre just after it had been set up. An interesting feature of the design of the centre is the way in which the computer screens are sunk into the desks and viewed through a transparent screen.

Significantly, all these centres have benefited from a substantial injection of funding for hardware, but all the centres rely heavily on goodwill and individual initiatives to ensure that they run smoothly. Finding funding for staff seems to be much more difficult than finding funding for machines - a common problem that I highlighted in my article "Lessons from the past, lessons for the future": http://www.camsoftpartners.co.uk/coegdd1.htm

Read the five case studies carefully, considering how you might benefit from the experiences of the writers, all of whom are language teachers and not technologists.

Let us have your views. Send us a message, using the ICT4LT Feedback Form.

Association of University Language Centres (AULC) in the UK and Ireland: http://www.leeds.ac.uk/languages/aulc/

Centre for Excellence in Multimedia Language Learning (CEMLL), University of Ulster: CEMLL's aims are described as: (i) developing teaching excellence and encouraging innovation in the use of multimedia resources, (ii) integrating the use of multimedia resources with face-to-face teaching, (iii) researching and evaluating the effectiveness of teaching in a multimedia environment, (iv) collaborating with colleagues within the University of Ulster and other HE Institutions and sharing good practice: http://cemll.ulster.ac.uk/

CERCLES (Confédération Européenne des Centres de Langues de l'Enseignement Supérieur): http://www.cercles.org/

Davies G., Bangs P., Frisby R. & Walton E. (2005 - regularly updated) Setting up effective digital language laboratories and multimedia ICT suites for Modern Foreign Languages, London: CILT.

IALLT (International Association for Language Learning Technology): Various publications on managing language centres.

Kronenberg F. (2011) Language Center Design, IALLT (International Association for Language Learning Technology), IBSN: 978-0-578-08725-2. This publication follows in the footsteps of the Language Center Design Kit and contains various chapters on designing or redesigning a language center. You may buy this publication either as a printed book or as a digital download (PDF).

LRC Project website: An EC-funded project (2001-2003) on Language Resources Centres: http://www.lrcnet.org/

See also the Bibliography and references section (below).

In 1992 the Modern Languages Faculty received a generous investment from Lyondell Inc., a multinational company (formerly known as ARCO) whose European headquarters is in Maidenhead, to create a language centre based around audio, satellite and computer technology. Realisation of the centre was carried out primarily by Richard Hamilton, Head of Modern Foreign Languages, over a six-month period. The money was spent in building alterations to a former pottery room, on a three-satellite dish system, on a standard audiocassette ASC language laboratory with 20 positions and the rest on a 16-PC Dell computer network and peripherals. The Lyondell Centre was formally opened by the British Minister for Higher Education in June 1993.

There were three primary objectives agreed by the school and Lyondell Inc:

All three objectives, if successful, would have implications for other schools considering new MFL ICT spending and for other companies considering similar, if more modest, investment but anxious nonetheless that there should be definite results.

The school's 1998 OFSTED report referred to the "exceptional" use of computers in MFL by pupils of all ages and abilities.

In May 1999 the Faculty won the CILT European Award for Languages (EAL) for the Lyondell Centre project:

In the November 2003 OFSTED report, a completely typical ICT session (no embellishments whatsoever, honest!) was graded "Excellent", which implies that the vast majority of the 50 ICT sessions per week are similarly excellent. The pupils (in this case Year 8) were utterly engrossed in the cycle of activities which brought together the four skills in a variety of ways - see below, Section 1.6.

As a result of progress made by the MFL Faculty, Lyondell funded several further projects: a multimedia upgrade for 16 computers (1996); a two-year videoconferencing project using the Internet, between Cox Green and the Lycée Rimbaud in Marseilles (1998); and the purchase of 40 new multimedia PCs (January 2000). As a multinational company working daily in a host of languages, Lyondell has enabled us to deliver MFL in ways which motivate pupils to see modern languages as rewarding and fun. The school is indeed grateful for Lyondell's support and encouragement.

The purpose of this case study is to highlight issues that have enabled us to make a success of the ICT element in the Lyondell Centre. Some of these appear trivial but have turned out to be disproportionately important. Hopefully, they will allow you to negotiate the inevitable learning curve more comfortably than we did.

Particularly if you are currently achieving above-average results, or if your school is oversubscribed, you may well wonder, as we did, why you should bother with Modern Foreign Languages/ICT at all. The cost of setting up ICT systems to support MFL, the time it will take to develop materials and keep the systems running sweetly (students can be very adept at making PCs malfunction), the stress for staff to adapt to new methods of working and the need to find physical space for a bunch of computers - all these factors combine to deter. ICT clearly has no monopoly of wisdom in the delivery of MFL, and the financial costs alone look boggling.

The potentially demoralising effect on staff is the most serious issue. We are used to being - hopefully - in control of activities, using resources that have probably been developed and accumulated for a number of years. We use pair work and group work to deliver MFL in as communicative a way as possible. Our credibility with students - a precious commodity in a critical age - derives from our fluency and expertise with these methods. And now we are to jeopardise all that so that students may thump away mindlessly at keyboards...

We started from absolute zero in PC expertise - we had just one BBC computer for administration. There was little expertise to tap: the County Council's MFL support services assumed minimal ICT access in MFL departments, and their support was based in any case on Acorn machines and, in a department of five, Year Head responsibilities constrained two colleagues' involvement. Time is always at a premium. When considering any addition to the Centre's activities, therefore, prime consideration has to be given to the impact on staff workloads. We had, and still have, no technician - everything has to function within the MFL staff's technical expertise and within existing teaching workloads.

Which of these factors apply to you / your school? To what extent are you and your school eager to include ICT in MFL?

Fortunately, the advantages of some carefully-structured ICT activities, which can be achieved at modest cost make it worthwhile: see Section 1.5, Hardware issues.

1.4.1 Discussion topic

To what extent is your school able to match the six essential issues listed above? If not, how might this affect your opportunities to integrate ICT into your MFL programme?

In 1997 I had 16 multimedia PCs, which obliged students to work in pairs. This worked reasonably well. In 1998 I was given (!) 25 old but seaworthy 486s which allowed students to have a PC each for non-multimedia work, and allowed all my MFL colleagues to have one, with predictably satisfying results in terms of greater output of resources and their familiarity with existing material. Now we all have laptops as standard teacher kit. The moral of this is clear: a very basic PC will do, and these are now at knockdown prices. Putting together 16 of these at £300 each will get you further than having, say, rather fewer very expensive laptops when you have a class of 32 pupils hungry to get their hands on a keyboard. The less appealing the PC, the less likely it is to get stolen too.

A few other considerations with hardware are important: cable ties deter theft, so does a seating plan backed up by five home security cameras at £30 apiece, each recording onto a cheap video recorder with a four-hour videocassette. If there have been no problems by lunchtime I simply press the record buttons again and the afternoon session overtapes the morning session. The next day I overtape yesterday's footage. As a deterrent it's effective, and if a class has been "excellent" I have INSET footage. The mouse balls have not been stolen because they are glued into the mice - obvious but necessary: one department had every mouse ball stolen. Most pupils like to be in the Centre and understand that "their" PC is used by 49 others each week, so we have their cooperation. Occasionally - and very rarely - individual pupils have to be banned for a time, but as the PCs also carry a few arcade-style games used as rewards the pupils have even less incentive to misbehave..

How much does your school want to spend on hardware and how far will this stretch?

There are two conflicting pressures: (a) Staff anxiety about ICT suggests slowly introducing software at a pace that allows your colleagues to grow in confidence; (b) on the other hand, you want to plunge in and buy a range of software to develop different skills.

In the pre-multimedia days of 1992, and with virtually no ICT skills ourselves, we decided to focus on Camsoft's Fun with Texts in our first year, as this allows you to tailor material to any course you are offering, for any age group in any language. We became very familiar with it, and so felt good about using ICT. This might seem laughably cautious now we are all supposed to be ICT boffins but the fact is, whereas children probably are ICT boffins, adults are more likely to be OK at word-processing but not confident about much else. So finding our way into ICT as a department together was of paramount importance. It still is: 15 years on we need to feel that our worth to the school lies in our ability to connect fluently with real children rather than with a keyboard, and this skill should be prized above all others.

This approach did mean, however, creating suitable material ourselves, a job that was done by two of us (out of six), and we kept about one lesson ahead of the pupils for our first year. We wrote textfiles that tied in absolutely with familiar courses, and existing word-processed material that we had inevitably typed for worksheets could be imported into Fun with Texts and quickly tweaked to produce worthwhile exercises. The seven different levels of activity with any text made all Fun with Texts work instantly differentiated. Students also got involved and started typing material for us. We now have several thousand files with more being written all the time (very largely by pupils as young as Year 8).

Shortcuts are possible when authoring for Fun with Texts as the program accepts any word-processed material. Most teachers have reams of that on their laptops already. You simply open the file in Word, save it as a plain text version and then the Fun with Texts Teacher Program allows you to import it into Fun with Texts where it automatically gives your text the presentational details you have decided in advance, e.g. we use Comic Sans in 22 point for KS3, reducing to 18 point for KS5. The point size minimises line breaks which tend to "throw" students and the KS5 material tends to be longer sentences so the smaller font size reduces the incidence of this. Another default is disabling (except for German) the need for capital / small letters to be accurate. There are several others you can choose. You save the file as a Fun with Texts file (an option accessible from the Save menu).

You now decide which words become gaps and which stay always visible. In our case, I highlight text I want to be remain on screen (normally the English) then right-click to provoke a drop-down menu, selecting Always Visible from the short range of options. You have to do this line by line, but it takes just seconds. In the case of a news article, you will probably want all the text to be reconstructed, so it takes even less time, as this stage is unnecessary.

Further material can be used with minimal use of your time: copy and paste a news article from the Web (into Word, then save as .txt), the range is limitless. The point of these prosaic details is to show that you can rapidly build up a collection of Fun with Texts files from a familiar starting point (i.e. Word) and so, particularly for KS5, they can be very topical and so motivating for students. Fun with Texts files are also tiny so thousands of them will occupy barely any hard drive space.

Got 35 pages of vocabulary in electronic form for a new syllabus? You're already 90% of the way to creating the whole syllabus in Fun with Texts. You've written a super new version of a writing test? Well, turn it into Fun with Texts in five minutes and let pupils tackle it electronically before their traditional writing test: their marks will improve, they'll feel better about themselves, more will opt for GCSE, and so on. You could even do the test electronically using one of the harder Fun with Texts activities and simply note their scores after a time limit.

That these are effective learning tools is suggested by the following tale: Graham Davies and I approached the publisher of a well-known A-level vocabulary book with the Fun with Texts version of every one of its 60 pages. "Would you like to promote this ICT aid?", we asked. They thought about it and concluded that nobody would buy the hard copy (of which they had a warehouse full) if they did. Enough said! Meanwhile the two Year-13 students who had typed it all into Fun with Texts and proofread each others' work gained A grades...

With the advent of multimedia the range of programs has become vast and there is a real danger that pupils will waste their time simply working out which buttons to click rather than learning anything to do with MFL. Although we look at a lot of software, we have settled on just a few packages, chosen specifically for their use with all age groups, which means we can author material for them. Pupils learn the mechanics of each program in Year 7, after which they forget the technology and focus on the language, becoming very independent and slick in the process.

The programs we use are:

What kind of software do I plan to use?

The Internet: Tales abound of aimless browsing and inappropriate emails, backed up by informal observation during ICT cover lessons. Being connected doesn't guarantee learning, so the question has to be asked: What does? Certainly our stable of interlocking activities, authored around a specific text, appeals to different learning styles and provides the greatest challenge through the inbuilt differentiation, even to the ablest pupils. The emphasis has to be on the content not the form. This is why we have stopped word-processing (endless problems with printer cartridges lasting five minutes and multiple copies run off by Joe Brainless) in favour of PowerPoint presentations which can be quickly copied to the teacher's computer and used with a data projector - thanks to the memory sticks that I can simply plug in to the USB port. See Module 1.5.

Email: Too open to abuse if done on school systems. Home-to-home after initial snail-mail contact and parental permission seems safest and leaves you less liable to embarrassment. See See Section 14, Module 1.5, headed Computer Mediated Communication (CMC).

Videoconferencing: A great idea, technically feasible especially if you have unlimited money. Did not work for us as the idea of regular one-to-one contact between students met the reality of different (and largely incompatible) school timings and adolescent embarrassment. Home-to-home email again… But it works for some people: see Section 14.1.3, Module 1.5, headed Videoconferencing: a synchronous communications medium.

Burning a CD of 30 PowerPoint presentations made by a class and sending it to the world at large. Think "pictures of pupils", think "child protection", think Copyright - and drop the whole idea.

Data projector linked to a computer: Allows whole-class delivery of ICT, Web-based or otherwise. Wireless mouse and keyboard allow pupil input without too much movement. Playing back sound requires mini-speakers very firmly attached to something solid. Great when it's not your turn to access the computer room. See Section 4, Module 1.4, headed Whole-class teaching and interactive whiteboards.

The unexpected decision by Lyondell to replace the Lyondell Centre’s 40 PCs with multimedia ones following our 1999 CILT European Quality Award created the opportunity for students at Cox Green to be centrally involved in the development of software resources and hardware configuration. A very hastily convened group of Year 11 and 12 students had already devised the shopping list of PCs and peripherals to meet Lyondell’s 72–hour deadline for ordering the hardware, thankfully met by the narrowest of margins. Could a much expanded group now tackle the development programme needed to maximise multimedia opportunities and ensure that the stand-alone PCs were foolproof in their display and secure from meddling? If successful, the school would then have an MFL multimedia system devised by students for students. This also made a virtue out of necessity as the school did not have ICT technician resources to drive this programme forwards; the eventual system had to be user-friendly for pupils aged from 11; and my ICT knowledge is still rudimentary, and I most certainly had the usual time constraints as head of department.

The students divided into two groups:

All the students involved in this project worked for free, knowing that their particular part in the project was linked to the language (French / German / Spanish) they were studying, and at an appropriate level. Participants’ rewards are a vastly improved familiarity with Key Stage 3 / KS4 MFL material, leading to rather better GCSE or A/S and A2 grades, and the satisfaction of solving the ICT challenges for those pursuing courses in this discipline.

PCs were loaned to students for their home use where needed, allowing both groups greater opportunity to work in peace and for more extended periods. This fuelled the pace with which the various challenges were tackled. External zip drives were used to get the multimedia work back into school for me and Yr 12/13 students to proof read.

The PCs have to be stand-alone, for reasons discussed in the earlier part of this case study. The challenge was to produce a workable solution even if I have been subsequently told by ICT wizards that it’s a clumsy solution. There has never been any pretence at elegance: the objective was to have a system which works with no technical support and which is 99% reliable, and the configuration of this system had to evolve within the students’ own ICT skills. As Windows steams down the road of multi-functionality, we wanted to block it; it felt a bit like buying a car and then taking the wheels off.

The security software Winlock is effective and good value. It comes in a network version, the advantage of which, even for stand-alones, is that the eventual icon display can be copied from PC to PC. Two profiles (Manager and User) are set up using Windows, the Manager's having a password, and the User's having none. Winlock then allows icons to be deleted from the User Start menu, as can icons at the bottom of the screen. They mostly are: our User Start menu offers just three tabs: French, German and Spanish, leading in turn to the icons for various software packages. A fourth tab required by Winlock is a dead end. The bottom of the screen has only the time and the volume control icon. The wallpaper is immutable. Run isn't there, so pupils cannot start their own programs by that route. Whole drives can also be made invisible to the user: by blocking user's access to A:\ (the floppy disc drive) and the CD drive, all associated problems of pupils trying to run their own programs (e.g. the threat of viruses) disappear, even before a physical floppy disc lock is attached - which in itself produces the problem of losing the key.

We tried putting icons over the wallpaper, but these could always be deleted, so the tabs, although showing smaller icons, were the safest place to locate them. A spare copy of the Start menu is on each PC anyway in case of malicious attack on the original, and it would take just seconds to overwrite the damaged one.

The exact process of configuring Winlock was videotaped by a student who obligingly pointed at the PC screen as he talked. This allowed me to configure the PCs in his absence. It’s a most valuable piece of video…

Software such as Fun with Texts, GapKit and Topguns invites the user to open a file. This gives access to the standard Windows browser that allows the user to navigate the entire PC’s hard drive, with potentially disastrous results. After many trials and tribulations, Group 1 realised that Winlock’s ability to render drives invisible to the user meant that if the C\: drive were partitioned into two, then the partition containing Windows and anything else we wanted to keep hidden could be made invisible. Using the excellent and idiot-proof Partition Magic we did just that: the C:\ drive contains just the operating system and is left at about 1Gb; the rest – which Partition Magic sorts out automatically (this will depend on the size of your hard drive) – is a new partition (automatically called D:\), used for all the software files that we want users to be able to see.

Partition Magic is easy to use: it tells you how big the C:\ drive has to be when you choose the size of the partitions. Another bonus: each partition creates its full whack of 64,000 clusters so you can minimise the wasteful effect of putting a small Fun with Texts file into a whopping great cluster and wasting 99% of that cluster. On a 4.3Gb PC – tiny by the standards two years on – we have not yet run out of space, but if space were at a premium, I could always split the new D:\ drive in half again and create another 64,000 clusters.

Partition Magic also automatically reconfigures your PC so that any CD drive links are changed from D:\ to the new E:\. The whole process takes about 20 minutes per PC.

On the new D:\ drive, all MFL software is contained within one folder named CALL (for Computer Assisted Language Learning). This means that copying material from the master PC using a CD writer is simplified and minimises the risk of copying stuff to the wrong part of the D:\ labyrinth. See below for more details.

Memorable icons were devised by students using software that allows existing icons to be altered. This actively helps classroom management, as younger pupils are more likely to click on “the blue fish” icon rather than something that Windows itself has provided. Groups of themed icons can also be produced: if we need four icons for GCSE themes 1–4, why not have four different coloured fish?

Fun with Texts, GapKit and Topguns all allow you to link icons to very specific folders, even though the programs are installed just once. Rather than have one icon for each program, which then requires the user to navigate extensively via the browser, we opted for many icons that target specific coursebooks or GCSE topics. The organisation of these is identical within Fun with Texts, GapKit and Topguns tabs, again for simplicity. Pupils pick it up in no time, helping their independence.

This consisted of an inner “core” of some 15 pupils generating multimedia exercises at home on PCs lent by me; 20 PCs were installed at school for whole-class testing of their work, with reported errors immediately rectified on a master PC with a CD writer. The majority of our 850 pupils therefore had an active part in the project and quickly spotted any errors in their peers’ work. The latest update of the texts, minus the soundfiles, takes up just 25Mb and can be copied in less than a minute to each PC, thereby overwriting the errors, as well as adding any latest batch of files to our collection. Interestingly, errors were spotted by the complete cross-section of the ability range. We cut on average several copies of the latest version each week and students copied them to the other PCs in relays.

GapKit : Pupils converted some 1500 Fun with Texts files (of 20 lines each) to .txt format and then chose one significant word per line as the gap to be linked to the whole-phrase soundfile, some thousands of which had been previously recorded by native speakers and professionally converted to .wav format. Pupils chose to work on the language appropriate to their language option and at an appropriate level. The resulting exercises were copied by pupils to the 20 PCs in school and beta-tested by appropriate classes for errors, layout suggestions etc.

Alterations complete, a second monolingual version of each was created very easily by altering the colour of the English text to white, so it is invisible. This had to be done line by line, but we (staff and pupils) used it as an opportunity to proof-read the finished version, and for a 20-line text it took perhaps 60 seconds. This way of producing differentiated versions of the same material was very time-effective and the monolingual nature of the resulting file really sharpens pupils' listening skills. This all took some 360,000 mouse clicks over several months.

As the result of an idea inspired at a Gifted and Talented Conference, we decided to create two further versions of each GapKit file. This time the entire phrase is the gap, rather than just one significant word with that phrase, so pupils have to type in half a dozen words to get that gap correct, rather than just one word. The bilingual version looks scary enough; the monolingual version (achieved in the same way as above) presents the user with just a series of red boxes, each representing a whole FL phrase.

Pupils thus have four versions of the same text to work with (single gap bilingual / single mono / whole phrase bi / whole phrase mono) and we have been stunned to witness the spirit of self-challenge which they muster; if you're ever having a jaded moment on a Friday afternoon and begin to wonder why you're in teaching, give them the challenge of the hardest GapKit version and marvel at the determination of youngsters for whom written accuracy is largely an alien concept. To see them punch the air with satisfaction when they get a whole line (complete with spaces and accent) correct, having heard only the native speaker and no English text, is rather nice. And this from the text messaging generation!

Curiously (once more) pupils of all abilities tackle the harder versions, more depending on their personality than linguistic competence. The usual "competitions" using the hardest version always produces a feverish bout of activity, and if pupils work in pairs and the reward is something very edible, then they're actually pushing each others' hands off the keyboard to type in the correct answers. Bliss.

A recent tweak to the programme allows the "cheat/reveal" button to be removed to thwart the idle. If you have configured your GapKit icons to target specific folders of material (very easily done), this facility can be applied or not depending on the target users. Keen Year 7s will probably use the Reveal button sensibly, cool Year 11s almost certainly not…

Topguns presents eight one-word boxes; users hear a soundfile and click on the relevant box to score. The same .txt pages were reduced to one word per line, again chosen by Group 2 pupils, and the soundfile link number added to each line. Beta-testing was again done by whole classes.

Soundfiles for French and Spanish occupy some 150Mb each language (at 22MHz), and 400Mb for German (recordings at 44MHz). To avoid installing these twice for GapKit and Topguns, they piggy-back each other in the same folder – neither program can “see” the text files of the other as GapKit files end in .gk and Topguns files end in .txt.

No greater evidence can be found for the enjoyment and motivation derived from the Lyondell Centre than the 800 letters of appreciation written to Mr John Pilavachi of Lyondell, who had secured the money for the multimedia upgrade. Pupils and students spoke enthusiastically of how they look forward to using the Centre:

These letters certainly put the project’s few frustrations into perspective.

This section was written by Richard Hamilton, Head of MFL, Cox Green Comprehensive School. Richard has now retired from teaching. Regrettably, language teaching at Cox Green School no longer enjoys the prestigious position that it used to have. Sadly, this is a trend that can be observed right across the state education sector in the UK. Questions relating to this section should be directed to Cox Green School at http://www.coxgreen.com

St George’s Academy serves the

market town of Sleaford and its surrounding villages. It operates in a selective

area: two single sex schools take the top 25% of the ability range (approximately).

However, in the last couple of years, an increasing number of parents have opted

to send their children who have passed the 11+ test to St George’s, which

offers a comprehensive, mixed education 11-18. Post-16, the three secondary

schools in Sleaford operate a common sixth form. Students remain enrolled in

their base school but can select any course on offer at any school. Currently,

there are about 500 students in the Sleaford Joint Sixth Form. St George’s

itself has grown to over 1200 students on roll.

St George’s Academy serves the

market town of Sleaford and its surrounding villages. It operates in a selective

area: two single sex schools take the top 25% of the ability range (approximately).

However, in the last couple of years, an increasing number of parents have opted

to send their children who have passed the 11+ test to St George’s, which

offers a comprehensive, mixed education 11-18. Post-16, the three secondary

schools in Sleaford operate a common sixth form. Students remain enrolled in

their base school but can select any course on offer at any school. Currently,

there are about 500 students in the Sleaford Joint Sixth Form. St George’s

itself has grown to over 1200 students on roll.

In 1992, St George’s became a grant-maintained school and in 1994 was granted Technology College status. Since 2010 it has been designated St George's Academy. St George’s wanted to adopt modern languages as a second specialism, but dual assignation was not allowed. All students, apart from a small number of disapplied Year 10 students, take a full GCSE course in one language. In Year 7, students begin with French and the top ability groups follow a second language in years 8 and 9 (German / Spanish in rotation). Each year, there are some dual linguists opting to continue with two languages in Key Stage 4. Post-16, the three secondary schools take it in turns to staff advanced level courses. In addition, St George’s is planning to offer language units for students on in-house GNVQ courses. There are currently five full-time and five part-time members of staff in the languages department and three language assistants. Teaching staff are supported by a Network Manager and an ICT Assistant, who are both experienced adult education tutors. St George’s also has a technician for in-house electrical and electronic repairs and maintenance.

In St George’s, modern languages have a long tradition that goes back to the early 1980s, when the Chair of Governors donated a substantial sum of money to realise a concept of language teaching which was then unique in Britain, if not Europe.

The Brealey Languages

Centre (BLC) was officially opened in 1985 as a purpose-built

building for modern languages. The attractive building originally

consisted of a central open-plan area - spacious enough to accommodate

up to four teaching groups - two classrooms and a number of utility

rooms. In the 1990s, three further classrooms were added as well

as a staff room and two offices.

The Brealey Languages

Centre (BLC) was officially opened in 1985 as a purpose-built

building for modern languages. The attractive building originally

consisted of a central open-plan area - spacious enough to accommodate

up to four teaching groups - two classrooms and a number of utility

rooms. In the 1990s, three further classrooms were added as well

as a staff room and two offices.

The octagonal central part has remained the heart of the Brealey

Centre. 37 round tables are arranged around the raised teacher's

console. Built into each one of these "mushrooms" are

three workstations with enough space to allow two students to

sit side-by-side. Each workstation consists of a computer and

a language laboratory audio station.

A particular feature of the Brealey Centre is that computer and audio facilities have always been networked. But whilst students now work on the fourth generation of computers, they are still using 30 of the original Tandberg language laboratory stations. In the mid-1990s, Tandberg installed a more advanced audio system at another 15 workstations.

The Tandberg equipment has proved to be very durable and reliable. Although the older tape-based system cannot easily be interfaced with the latest computers, it still fulfils its main functions of allowing students to develop their listening and speaking skills. Staff also still like the convenience of being able to play or copy standard audiotapes from their console to all students, with commercially as well as in-house produced recordings.

However, the Brealey Centre could not remain in the analogue audio age but had to move on and become digital. Three major stages in the development of the Brealey Languages Centre can be identified:

From 1985 to 1994, the only interactive links from the BLC to the outside world were dial-up modem connections. There was one successful attempt to extend the BBC Acorn network to other parts of the school but with the first classroom-based PC networks being installed elsewhere in the school, this pilot was not taken further. Staff in the BLC could receive and record radio programmes and satellite broadcasts; some of the latter were used in classroom but not in the Centre. In those days, Fun with Texts was used extensively by staff, who built up a large number of files over the years.

St George’s started networking the whole school with industry-standard hardware and software in 1994. Since then, the BLC has housed all St George’s file servers and other central services, including backup devices. However, for the first time in its history, the BLC had to fall in line with wider College developments, as its facilities were much in demand by other subject areas taking up bookings not required by modern languages.

In those days, each language class was allocated one session in the BLC whilst still retaining its classroom. This "double room allocation" allowed teachers to move students into the BLC when they were ready to start computer-based exercises and to take them back to the classroom when they had finished. Under this system, some computer time was seen by other departments as being "wasted". Modern languages teachers, on the other hand, argued that it would have been inappropriate to take their students into the BLC without preparing them first – a judgement all teachers are expected to make today, namely when and when not to use ICT in subject teaching.

The new whole College Network enabled languages staff and their students, at long last, to access computer based teaching materials in networked classrooms in the main school building. To their delight, three further classrooms were added to the BLC during stage 2.

Since the early 1990s, Brealey Centre staff have been actively involved in creating online materials for modern languages, starting with text-only format and then gradually adding graphics and sound. At the BLC, Fun with Texts remained a firm favourite, its use made even easier when the old DOS version was replaced with the Windows edition. The development of multimedia, heralded as a revolution when still confined to CD-ROMs, was accelerated through the increasing power of computers and access to the Internet and the World Wide Web.

The next milestone in the use of ICT in languages (and other subjects) was the installation of an ISDN line to give staff and students faster and networked access to the Internet (filtered). The Internet access capacity soon had to be doubled, taking advantage of BT’s fixed price package for schools (unfortunately, cable access will not be available in Sleaford in the foreseeable future).

Teachers, encouraged and supported by the ICT support staff, soon began to experiment with Internet technology to create a new brand of teaching materials: browser-based worksheets and exercises. Staff still use applications software (the use of a spreadsheet in German is one of the modern languages examples on the TTA ICT Needs Identification CD-ROM), Fun with Texts, Chatter and other packages to reinforce what has been introduced in the classroom. However, the rapidly developing Web technology, with animated GIFs, interactive forms and many other features, has a great potential for language teaching (and testing). The ICT support staff have created a template for showing video clips, which are selected and captured from the Internet and then processed and streamed in-house. On the St George’s intranet, students can browse through information about the next German study trip and then extend their search by going to www.entry.de, one of the many websites they can use to find out more about the towns they will visit.

At the BLC, the drive to enrich office applications software, CD-ROMs and dedicated packages with Web-based materials is accelerating. Two factors have facilitated this development: access to the Internet at home and the National Grid for Learning. Future developments at the BLC will be shaped by these and other government initiatives such as Computers for Teachers, ICT Training for Teachers (NOF), Key Skill ICT and local, regional and national targets. St George’s is particularly interested in the impact that the National Grid for Learning has on students and teachers, their teaching and learning styles and students’ levels of achievement.

St George’s is actively involved in implementing Lincolnshire’s contribution to the Government’s National Grid for Learning initiative: NETLinc, a project designed to build up a shared central infrastructure and a county-wide educational intranet with filtered Internet access.

Under NETLinc, each participating school is fitted out with a computer network and high-specification workstations, linked by an ISDN line to central services. On entry into the Lincolnshire education system, each child is given a unique NETLinc user identity which he/she can use to log into the system on any NETLinc computer. It is envisaged that users will keep their NETLinc IDs for all Key Stages and beyond for life-long learning. In the first two years, mostly primary schools were connected to NETLinc. St George’s has adopted the NETLinc user identification scheme – all new Year 7 students have to do is to change their password when first logging on.

Like the national literacy hour, the National Grid for Learning has made a significant difference in Lincolnshire. Students leave NETLinc primary schools with higher levels of ICT skills, understanding, and knowledge; they have local and wide-area network and Internet experience. Some of them can even create Web pages. Secondary schools need to take their new intake’s increased levels of prior achievement and ability into account in their Key Stage 3 ICT planning and schemes of work. Some secondary schools, however, face problems, as their own ICT facilities are older than those of NETLinc feeder schools. If that is case, Year 7 students have to "step back" and work on older computers with earlier software versions, which makes it difficult if not impossible for them to retrieve primary school work stored in their NETLinc home directories. Different hardware and software provisions currently impede academic progression over the Key Stage 2 to Key Stage 3 transition. NETLinc aims to overcome this problem. The computers in the Brealey Centre do not quite match the specification of NETLinc workstations and, more importantly, the College’s software platform is one version behind NETLinc. St George’s has resolved this issue by installing the software used by NETLinc on another section of the College network.

The next major challenge under the National Grid for Learning is the Broadband Project. As part of the East Midlands consortium, NETLinc will install broadband connections in 10 pilot schools in the coming year. St George’s aims to upgrade its two ISDN lines to broadband ahead of the government’s target of 2002. However, whilst all computers in the Brealey Centre passed the millennium test, some of them will fail at the broadband hurdle as they are not powerful enough to cope with the amount and speed of data flow. No decisions have been made as yet but the most likely solution will be to upgrade 15 workstations in the Brealey Centre into a broadband section and, hopefully, to install Tandberg’s latest software suite to extend language-laboratory-type facilities across the whole College Network into other subject areas. The faster the pace of technical developments, however, the more important becomes the partnership between technical support and teaching staff: only by working together can they provide a teaching and learning resource that is reliable and innovative.

St George’s twin mottoes are "Aiming High" and "Excellence for All". St George’s places particular emphasis on ICT. In its drive to raise standards, St George’s aims to extend students’ learning styles and to promote more independent learning. The latter will be fostered in College across the curriculum but also needs to happen at home. The College sees ICT playing a major role in facilitating this "new learning". Adopting a twin-track approach, St George’s will: (a) increase the number of its open access ICT suites, including a section in the BLC, and (b) make parts of the curriculum available online via the Internet. This "opening" of ICT facilities has major implications for how they are managed and protected. For several years now, students have been allowed "shuttle discs" between school and home. In that time, only a few virus alerts were registered – luckily, these were not "attacks" and could be cleaned up quickly (see the Appendix: Viruses). However, the envisaged open system requires better protection not only against viruses but also against outside hackers. More importantly, tried and trusted teaching and learning resources need to be re-written so that they can be delivered over the Internet and accessed by individual students working at their own pace.

As a school, St George’s cannot replace computers every year but needs to get good use out of them over a number of years. The computers in the Brealey Centre are not of the latest specification but - for staff - powerful enough to run networked multimedia software and to cope with animated pages accessed on the Internet. Students, of course, have higher expectations of ICT workstations; they would like to work on faster, more powerful machines.

Further investment needs to be justified by the impact it has on standards in modern languages, on students’ levels of achievement, measured not in grades alone but in value-added terms.

At St George’s, we regard the quality of teaching and learning rather than the specification of our ICT equipment as paramount. Looking ahead, our management and staff will need to resolve a number of issues:

At St George’s, we have not found all the answers yet but we are working on them – and we would like to hear from anyone interested in a continued professional discussion of ICT4LT.

This section was written by Berthold Weidmann, who has now left St George's. Questions relating to this section should be directed to St George's Academy: http://www.st-georges-academy.org

The English Department at the University of Münster - with about 45,000 students one of the biggest German universities - is an institution of higher education which offers MA and PhD degree courses in English Language and Literature as well as ELT courses for prospective secondary school teachers. The vast majority of our students have had at least nine years of English before entering university. In addition, most of them have spent at least six months in an English-speaking country by the time they finish their studies, either at a university or as assistant teachers. They can, therefore, be considered highly advanced students.

With this history, it should come as no surprise that the English Department's Self-Access Centre (SAC), which opened in the spring of 1993, is quite unlike self-access centres at other institutions, as it never placed much emphasis on computer-based language learning in the traditional sense. The students rather use the facilities to pursue their literary, linguistic or socio-cultural studies, or to just meet peers and speak English. The SAC serves as a:

In short, the SAC is more than just a mere computer language lab, but rather a place where the students can access resources of various kinds.

What makes the SAC a remarkable - maybe even a unique - multimedia language centre, is its organisational set-up: the SAC is largely run by students for students.

Shifting the responsibility of administering the centre to the learners was essentially motivated by two factors. On the one hand, there is no denying that the decision was induced by financial constraints. While it proved to be relatively easy to obtain funding for setting up the centre - equipment and furniture were jointly financed by the Ministry of Higher Education and Münster University - these institutions were far more reluctant when it came to providing the SAC with a permanent staff. Except for the first few months, when one lecturer's teaching duties were reduced to make material design possible, the SAC's personnel has always consisted of just two student assistants who work for a total of 16 hours a week. Since an enormous variety of time-consuming tasks are associated with running a self-access centre (maintenance of equipment, material development, documentation and installation, learner-training, supervision, etc.), it was clear right from the start that this would not suffice and that we would have to rely heavily on student volunteers.

On the other hand, the decision was based on the conviction that if we take principles like learner autonomy seriously, we must practise what we preach. Therefore, the students were involved not only in the planning stages, but also later on in the negotiations with computer companies, and when decisions were made as to what kinds of materials were needed and how the centre should best be organized. A student Support Team is now in charge of the Sac's organisation. The Support Team decides what materials to purchase, conducts software-training courses and organises social events. Individual students even offer workshops or tutorials, and develop materials for their peers (e.g. CALL exercises, program documentation and customised manuals). Furthermore, a comparatively large number of student volunteers supervise the centre during opening hours. For further details on student activities in the SAC, see the information below: Section 3.4.

Regarding the technical equipment in the SAC, it must be pointed out that the centre is currently (April 2000) under (re-) construction, a process during which most of the original equipment will be replaced and the number of workstations will be doubled. In addition, one of the new rooms will be equipped with a data projector, so that the facilities are available for use in regular university courses while at the same time being accessible for self-directed learning.

When the SAC was being set up, it was clear that only a tailored centre would suit our students' needs. Ready-made solutions proved to be too expensive, and they also lacked the flexibility and openness to allow for various paths of study. Therefore, the technical equipment was obtained from various sources. After the reopening of the centre (summer 2000), it will comprise

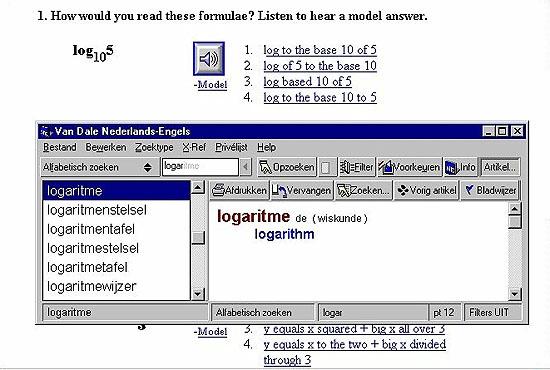

The computer programs offered include:

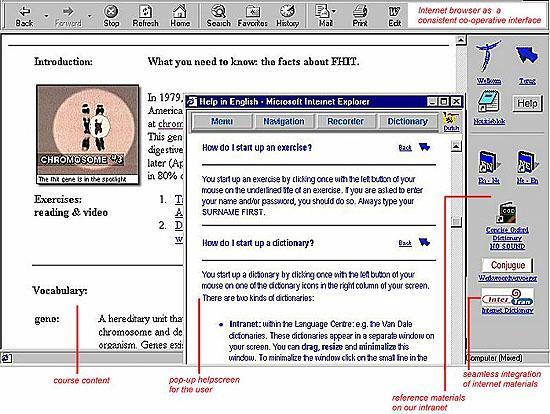

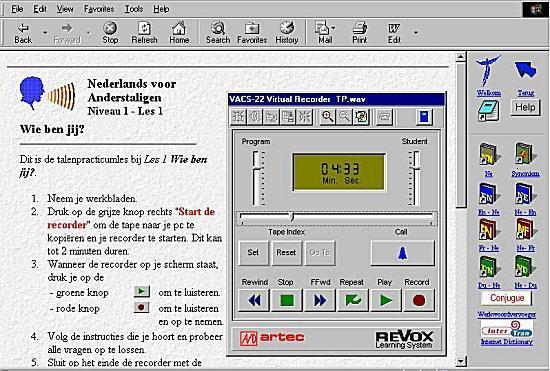

Since neither student supervisors nor SAC users are, as a rule, computer experts, except for maybe the notorious computer whiz, the computer network has been organised in an as 'learner-friendly' way as possible. Otherwise, many a student might have shied away from using the computers, or would at least have given up when faced with difficulties. After the first flush of enthusiasm, there might have been a slackening of interest, and the place might soon have become rarely frequented. Access to the materials, therefore, had to be foolproof and transparent, and we had to make it impossible for the ordinary user to manipulate configuration files. For these reasons, a user-interface, the Guide to the SAC, was developed which standardises both the layout of the computer screens and the paths of access to the application programs, so that programs can only be launched from the interface. Moreover, the Guide provides access to the catalogue of self-study materials, offers tutorials for computer novices and first-time users of the facilities and includes an informative hypertext system which lines out possible paths of study and directs the learners to topic-related materials. It also contains a calendar with information on social events in the SAC. While the original version of the interface was programmed with ToolBook, an HTML-version has now been designed.

As indicated before, student activities in the SAC are manifold, which makes it hard to single out the most noteworthy studies pursued. The following examples, therefore, represent a random selection, which does not necessarily reflect the full scope of projects and/or activities.

Student initiatives have led, for example, to the formation of various workshops. Several creative writing workshops, such as a Poetry and Prose Workshop in winter 1998/1999, have been held from which public readings and even printed publications emerged, such as "UN-TITLED" (1999) by C. Ryan, R. Swadzba & A. Wilke. In addition, a native speaker conducts a workshop for students who need assistance with their assignments. This workshop started out as an essay-writing tutorial known as The Write Place, and then developed into an institution which offers learners a platform for discussing their linguistic problems, as well as other problems. Other workshops include the Film Club, which presents Weekly Film Features together with an introduction to the respective movies, and several technology-related interest groups, e.g. HTML Programming, email and the Internet. There are also regular student-administered introductions to the SAC.